The need for EAL specialists

27th February 2018

2017 performance statistics show that, for the first time, EAL pupils outperformed native speakers at GCSE on all DfE measures. However, as EPI point out in a recent report, we desperately need national structures to create and retain EAL specialists. Even though EAL outcomes are high on average, this masks what are likely to be wide variations in outcomes between EAL pupils with different characteristics. Ultimately, this risks distracting public attention away from the need for improved education policies.

Why does it matter?

At first glance, attainment and progress data seem to suggest the system is working for pupils with EAL. In 2016, as a group, EAL pupils made above average progress and were more likely to achieve the English Baccalaureate than pupils with English as a first language. However, looking at averages for EAL pupils can divert attention away from those EAL pupils who do less favourably, and need support.

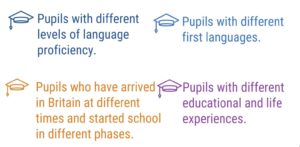

As EPI point out, pupils with EAL have a diverse range of characteristics. The group includes:

These forms of diversity can lead to a range of outcomes for pupils with EAL, around the (albeit high) average for this group. As the EPI show in their report, there is huge internal variation between pupils with “different first languages and different times of arrival”. Slovak pupils, for instance, fall behind by as much as 29 points at KS2 compared to the national standard for all pupils if they join in Year 6.

Furthermore, as EPI highlight, progress data for pupils with EAL does not necessarily tell us whether these pupils are meeting their academic potential. If pupils sit baseline assessments before they have proficiency in English, their starting point will be recorded as artificially low.

progress data for pupils with EAL does not necessarily tell us whether these pupils are meeting their academic potential. If pupils sit baseline assessments before they have proficiency in English, their starting point will be recorded as… Share on XConsequently, later measurements may overestimate progress.

Echoing EPI’s recommendation, it’s essential that schools use EAL specialists to effectively support pupils and conduct baseline assessments. Giving teachers access to effective initial and expert training on EAL would help to equip them with the necessary skills. In turn, this would help pupils with EAL to reach their full academic potential.

Where are the policies?

Unfortunately, as EPI report, there are currently no policy mechanisms to create new EAL specialists.

During my own initial teacher training, I was desperate for better training on how to teach pupils with EAL. This was because, in my first school, a large minority of my pupils spoke English as an Additional Language and needed language support during lessons. What’s more, I would have jumped at the chance to become a specialist in the area. Feedback from others in the sector suggest that my experience is not unique. In 2016, NQTs reported that their training did not prepare them to teach pupils with EAL. Experts have also berated policymakers for the shortage of specialist leaders in education for EAL. As our Director Loic argues, teacher appetite should be the driving force behind improved CPD, and if teachers are eager to strengthen their expertise on EAL, the government should provide a teacher training framework to support this.

What can we learn from other countries?

Policy borrowing is a questionable practice. International policies that are plucked from their cultural contexts and slotted into ours will not necessarily be successful. However, English policies on EAL compare starkly with those in other English-speaking jurisdictions. EPI’s analysis of policies from New York, Minnesota (USA), Alberta (Canada), New South Wales (Australia) and New Zealand showed that these jurisdictions focussed EAL policies on:

- Specialist roles, staff development and specialist graduate qualifications.

- Guidance on defining what EAL support should be.

- Providing sufficient provision in areas where EAL populations are sparse.

- Parental engagement.

In comparison, policies in England do not place emphasis on these areas. The Department for Education does collect teacher-assessments of language proficiency for pupils with EAL. However, there is no clear government guidance as to what EAL support should look like. Furthermore, the Ethnic Minority Achievement Grant was abolished in 2011, meaning that funding is no longer dedicated to supporting this group, many of whom speak English as an Additional Language. Whilst we cannot simply copy international policies, EPI’s comparative analysis does point to potential education policy gaps in England.

Where do we go from here?

EPI recommend that policymakers “generate and maintain EAL expertise in schools.” The ways they suggest this could be done include:

- Investing in EAL as part of initial teacher training. This would help to give trainee teachers a better foundation of skills which may inspire them to become EAL specialists in future.

- Creating more graduate level specialist qualifications.

- Establishing specialist roles, including specialist leaders of education for EAL.

- Specialist programmes focussed on developing staff to support pupils with EAL.

Average attainment scores for pupils with EAL do not tell the whole story or negate the need for improved EAL support. Education policymakers can create an environment that better supports pupils with EAL. Filling the gap in specialist expertise is a good place to start.