Period poverty: do DfE statistics speak for themselves?

3rd April 2018

The Department for Education’s recent report presents school absence statistics to investigate whether “disadvantaged girls are not attending school due to not being able to afford” menstruation products. However, we must avoid downplaying the reality of period poverty like the Department’s report appears to. DfE absence statistics don’t tell the whole story.

What do DfE statistics tell us?

Whilst the Department’s statistics show absence rates for different groups and ages of pupils, they fail to tell us much about period poverty or the experience of menstruation in school more generally.

Although the term ‘period poverty’ is often used to discuss girls who are missing school due to being unable to afford menstruation products, period (or menstruation) poverty is commonly defined as “poor menstrual knowledge and access to sanitary products”. Whilst the Department acknowledge that the term “has been attributed to a number of societal issues,” focussing on school absence data lends itself to confusing one of the impacts of period poverty (school absence) with period poverty’s prevalence. Put simply, looking at school absence data will not tell us whether period poverty exists, how many girls are experiencing it or what impact it has.

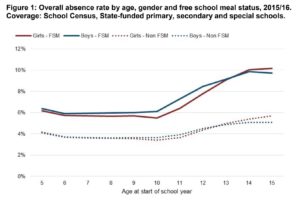

looking at school absence data will not tell us whether period poverty exists Share on XThat said, school absence data is useful for telling us the recorded reasons for different pupils’ absence. The Department’s data shows that both boys and girls on free school meals (FSM) generally have higher rates of absence than non-FSM pupils.

Figure 1

Source: https://bit.ly/2GMZyCG

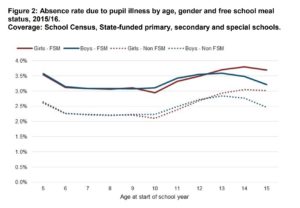

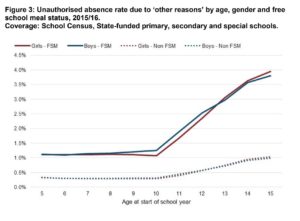

This trend is also apparent when we look at reasons for absence. FSM boys and girls generally have higher rates of absence due to illness and unauthorised absence due to ‘other reasons’ compared to non-FSM girls and boys.

Figure 2

Source: https://bit.ly/2GMZyCG

Figure 3

Source: https://bit.ly/2GMZyC

So, what does this tell us about period poverty? Not much. We can’t verify the validity of the reasons given for absence and we don’t know what ‘illness’ or ‘other reasons’ encompass. As I have previously argued, the stigma surrounding both poverty and menstruation may prevent girls from being honest about their experiences. Furthermore, this data doesn’t tell us about other impacts of period poverty. Even if some girls experiencing period poverty have good school attendance, does that make period poverty ok?

If some girls experiencing #periodpoverty have good #schoolattendance does that make #periodpoverty ok? Share on XHowever, it is interesting to note that both FSM and non-FSM girls’ absence rates, due to illness, continue to rise from age 10 to age 14 (figure 2). They also surpass both FSM and non-FSM boys’ absence rates between the ages of 12-13 and onwards. Given that the average age to start menstruation is 12.9 years, it would be useful to investigate the reasons behind this trend. For instance, it may be the case that the stigma surrounding menstruation has an impact on both FSM girls and non-FSM girls attending school.

What about wider issues?

Whilst girls’ school attendance is important, the ultimate goal of ending period poverty shouldn’t just be about reducing absence rates. International research from poor-resource settings suggests that insufficient access to menstruation products and poor menstruation education is often associated with stigma, low mood and poor educational engagement .

This resonates with findings from the UK. In 2017, Plan UK found that for 14-21 year-old girls:

- 1 in 7 girls (15%) have struggled to afford menstruation products.

- More than 1 in 10 (12%) have had to use items other than menstruation products to stem their menstrual flow (i.e. they have had to improvise menstruation towels/tampons).

- Almost half (48%) are embarrassed by their periods.

- Only 22% feel comfortable to talk to a teacher about their periods.

- More than a quarter (26%) said they did not know what to do when they started their period.

- 1 in 7 girls (14%) said they did not know what was happening when they started their period.

These findings should concern education policy-makers. It feels like the DfE missed an opportunity to investigate how period poverty, and menstruation more generally, affects girls in school. Given that the Sex and Relationship Education guidance is set to be updated in 2019, it would have been useful to explore how SRE could be adapted to tackle menstruation stigma and better support girls.

Unfortunately, by analysing absence statistics only, the Department has:

- Failed to find out how period poverty affects school attendance.

- Ignored the wider impacts of period poverty.

- Failed to investigate how menstruation impacts girls’ educational experiences more generally.

I worry that the Department’s report will provide fuel for both those who deny period poverty’s existence/importance and those who stigmatise menstruation. This is just one of the worrying social media comments I have seen since the report was released:

We need to challenge the stigma surrounding period poverty and menstruation. Absence statistics do not nullify girls’ experiences and further investigation into period poverty, and wider menstruation education, is needed.

Where do we go from here?

The DfE’s inconclusive pupil absence statistics are not the end of the period poverty debate. Campaigners have called out the DfE’s report for providing “superficial” data and the Department is set to investigate school leaders, pupils and parents’ views about period poverty. However, I think there’s more to be done:

- Policy-makers, teachers, parents and people in general should challenge the stigma around menstruation in schools and society more widely. By talking openly and positively about menstruation, we are likely to create an environment where period poverty is unacceptable.

- Policy-makers should investigate girls’ experiences of period poverty, and menstruation more generally, to inform changes to Sex and Relationship Education.

- Policy-makers should consider the impact of poor access to menstruation products/poor menstruation education on wider issues such as girls’ self-esteem, school engagement and physical health. Such investigations should inform plans to offer free menstruation products to girls who have poor access to them.

Period poverty is a real problem. Solving it will be about so much more than tracking inconclusive statistics on pupil absence.

Period poverty is a real problem. Solving it is about much more than DfE pupil absence statistics. Share on X