How London learned from its teacher shortage

17th July 2014

Whether London schools in the late ‘90s were really dens of despair is debatable. But what isn’t up for discussion is that a severe teacher shortage gripped the city during the early millennium.

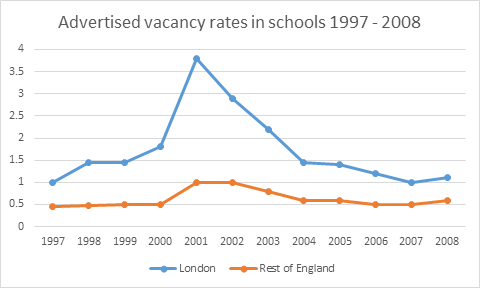

Though London has always suffered higher vacancy rates than the rest of England, the figures rocketed after 1997 up to a peak of 3.7% of positions being advertised at any one time in 2001.

People recruiting in this era describe the difficulty of trying to get someone – anyone – in front of a class. Endless supply teachers, staff worn ragged doing cover, the stuff of nightmares. Even when I began teaching in 2006 the school had advertised twice and interviewed 11 people, none of whom were suitable.

In part, the vacancies were a product of Labour government policies limiting class sizes alongside large-scale EU immigration. However, policies such as the Overseas Trained Teacher Programme, the Graduate Teacher Programe, and the introduction of TeachFirst, helped stabilise rates and by 2004 they were falling back to pre-2000 levels.

How did London turn around the shortage?

The Overseas Teacher programme sucked in teachers from other countries – most notably Australia and South Africa. They were mostly young, dynamic, and brought new teaching methods that others learned from. The Graduate Training Programme and Teach First brought what has been described by one head teacher as a ‘blood transfusion’ of new staff.

Beyond the recruitment programmes, teacher retention was supported by the introduction of a London pay rate. In the era of skyrocketing houseprices, many teachers couldn’t afford a home and so left to buy properties elsewhere. Upping the pay rate caused people to rethink their economics – or at the very least buy a house on the outskirts of London and commute to the inner-city, rather than abandoning it altogether.

Evidence for the success of ‘key worker housing’ policies during this time is thin on the ground. (Not because the programme was poor, just that no one seems to have collected any). But anecdotal evidence suggests the very ‘promise’ of key worker housing, plus the additional London pay, made city-living more realistic.

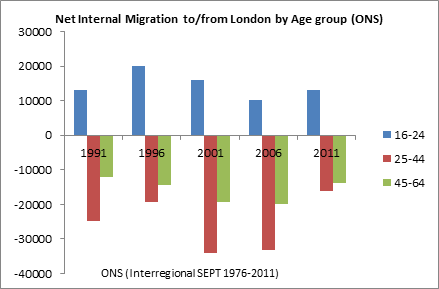

Teach First in particular utilized the fact that most university graduates want to move to London post-graduation. Surveys suggest 50% of final year students aim to move into the capital. No other part of the country garners more than 5%. Teach First’s attractive two-year package, during which time trainees are paid to train in challenging schools that were otherwise struggling to fill vacancies, also helped plug shortages – and made teaching in the then-struggling city into a ‘cool thing to do’.

A potential downside of focusing on younger teacher was the dearth of middle managers. The census shows that the peak age for moving to London is 21-24; however the peak age for leaving is 25-32. With people in heads of department positions fleeing, many London NQTs found themselves taking on positions of responsibility early in their career. Though this sounds problematic the professional development opportunities being offered as part of London Challenge meant energetic new entrants often found themselves in exciting and well-supported positions of influence which motivated them to stay in the profession, and to excel.

Conclusion

Conclusion

The London teacher shortage was therefore hellish for Heads trying to get bodies in front of classes. But the outcome of the crisis seems to have been a stronger system.

Location-based pay, young teachers being trained to take on responsibility, access to housing: each mattered for getting London back on track. These lessons might not apply everywhere. In other parts of the country, for example, teachers aren’t so heavily priced out of the property markets. But it does show that a crisis in recruitment doesn’t have to last forever – and that out of the dark really can come significant light.

More London Blogs:

- Professional development and professionalism: The symbolic value of CPD

- Show me the money: Was London’s success all about the extra money?

- More than the sum of its parts: How London’s boroughs helped drive success

- London Schools: Now we have a full(er) picture

‘Lessons from London Schools: Investigating the Success’ is a Centre for London and CfBT report and we are grateful to both organisations for giving us the opportunity to carry out an in depth study of this crucial topic.

The views in this blog are my own and whilst my analysis is predominantly based on the CfL/CfBTreports, not all the data I have presented here is necessarily in the report.

Comments