ADHD: Dreaming, distracted or wired differently? Part 1 – causes and symptoms

3rd April 2019

By Abi Angus & Ellie Mulcahy

Like many other women with ADHD, I received my diagnosis as an adult. The suggestion that it may be worth getting assessed for ADHD was something of a surprise to me; I had supported young people with ADHD diagnoses in previous roles and found it hard to match up my experiences with these hyperactive, quick thinking, impulsive teenage boys.

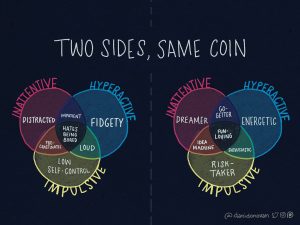

However, as I went through the diagnosis process and read up on the topic, I began to recognise ADHD traits in myself. I realised that the version of ADHD I had seen (and thought was fairly universal) belonged to just one of three subtypes – the hyperactive-impulsive subtype, and that the full definition of ADHD captured a broader range of experiences and symptoms, including the symptoms I was experiencing.

The three main subtypes of ADHD are:

|

A lack of understanding of the different forms of ADHD can result in underdiagnosis or support that doesn’t meet needs properly. In this blog we’ll look at some common misconceptions held about ADHD, debunk some myths and hopefully make ADHD a little easier to understand along the way. A lack of understanding of the different forms of ADHD can result in underdiagnosis or support that doesn’t meet needs properly. Share on X

So what is ADHD?

ADHD is not a mental illness, but often co-exists alongside poor mental health. It is not a learning difficulty, but can make learning harder. ADHD isn’t automatically classed as a disability, but the symptoms for some people can impact on their ability to function in day to day life, falling under the Equality Act’s definition of disability. It’s useful to view ADHD through a social model of disability framework, understanding that those with a diagnosis are neuro-atypical and are likely to require support or strategies to navigate a world that isn’t always built for neurodiversity.

People with ADHD experience symptoms that are often understood by neuropsychologists as an impairment of executive functioning. Executive functions are the processes that control how we plan, order and complete tasks, they direct how we respond to new situations and work towards end goals. An analysis of studies exploring the link between executive functioning and ADHD published in 2005 reported that people with ADHD demonstrated ‘significant impairment’ on executive functioning tasks, with particular difficulties in planning, working memory and response inhibition.

What does ADHD look like?

Hyperactivity, impulsivity and inattentiveness characterise ADHD but can be experienced in a range of ways, some unexpected.

Hyperactivity might make it difficult to sit still. This could impact on someone’s ability to stay in meetings or at a desk for long periods of time but may be less noticeable, involving fidgeting or fiddling with items out of sight. While hyperactivity is usually understood as physical, many people with ADHD report difficulties in relaxing mentally, often feeling restless or edgy.

Impulsivity can make listening to people without interrupting extremely difficult. It may also make it harder to keep a handle on emotions and to think through and plan tasks, resulting in getting frustrated quickly.

Inattentiveness may result in someone becoming easily distracted or finding it difficult to take notice of details, making it hard to follow instructions. Tasks can be difficult to organise and maintaining motivation can be a challenge so people with ADHD may find themselves starting more projects than they finish. Difficulties with attention can also result in frequently lost and misplaced items as well as issues keeping track of time and finances.

These difficulties, alongside issues with executive functioning and poor working memory, can affect day to day planning, structuring and organisation of school, work and life and often result in people feeling like they are working harder to keep on top of tasks that appear straightforward to others.

The causes of ADHD: myths and truths

A variety of factors have been suggested as causes of or risk factors for ADHD. Current research has identified risk factors such as premature birth and epilepsy alongside strong genetic contributors. However, misconceptions about the cause of ADHD – or even its status as a neurological disorder are widespread.

A US study found that two thirds of adults ‘had heard of ADHD’ and of those, nearly a fifth (18%) did not believe that ‘ADHD is a real disease’. This lack of knowledge creates the perfect environment for misconceptions to flourish. A commonly held belief is that ADHD symptoms are a result of poor parenting, that if parents were better resourced to maintain boundaries and discipline their children then these young people would be able to stay still, maintain attention and think through consequences before acting. While positive reinforcement and secure boundaries will help support young people with ADHD, this won’t remove difficulties entirely.

Neurological studies have found considerable differences in the brain structure and chemistry of people with ADHD compared to people who are neurotypical, contributing to the evidence that ADHD is indeed a ‘real’ disorder and not something caused by a lack of boundaries or adults’ intolerance for ‘boisterous’ children.

A real diagnosis with real impact

As with any life-long diagnosis, people’s difficulties and support needs may change over the course of their life and can differ depending on work and home environments.

If we use the social model of disability as a lens, we can understand that some situations will be harder to manage for those who are neurodiverse and can ‘disable’ people, whereas other situations may give people space to make the most of their strengths and coping mechanisms they have put in place. I, for example struggle in a workplace that relies on tight punctuality and sets long tasks with no endpoint or deadlines, whereas in flexible environments with freedom to manage my own workload, the things I find difficult are far less obvious.

It’s been important to remind myself that a diagnosis of ADHD isn’t proof that I am ‘broken’. Being neuroatypical isn’t an inherently negative thing, it just means that the way we understand and move through the world may look a little different. Neurodiversity can also bring benefits; a unique perspective can be valuable and some ADHD traits can be positive in certain situations. Being neuroatypical isn’t an inherently negative thing, it just means that the way we understand and move through the world may look a little different. Neurodiversity can also bring benefits Share on X For example, someone who finds it difficult to stay on task for long periods of time may be skilled at switching between projects or pieces of work flexibly. The illustration (below) by an artist with ADHD highlights how neurodiversity can provide challenges while also adding to a set of skills.

A diagnosis can also be useful to explain why tasks that others seem to complete with no issues can feel like a marathon, providing an understanding that the things you struggle with aren’t due to character flaws or lack of effort. For me, receiving a diagnosis of ADHD meant I could consider the labels I had received and given myself throughout education and adult life with a new perspective.

Where previously I had been ‘scatty’, ‘forgetful’ and ‘disorganised’, these can now be understood as difficulties caused by differences in my neurological makeup – not an excuse to avoid tasks that I find hard, but a reminder that ‘just trying harder’ won’t be enough without additional support or coping strategies.

Read part 2 for a more detailed look at the neurological differences found in people with ADHD, a look at gendered differences in identification and diagnosis of ADHD and some practical implications for support.

Comments