Like many, I welcomed today’s news of the

amazing results achieved by Thomas Jones School. It’s always fantastic to hear about schools succeeding against the odds and transforming disadvantaged pupils’ life chances. No question about that. However, the mention of “up to two hours” homework a-night raised questions for me; Thomas Jones is a primary school.

I’m sure the school actually uses homework carefully and doses it appropriately- the article clearly says “up to” two hours but this blog is not about Thomas Jones School. It’s about whether it would be ok for a primary school to set 2 hours homework. I assumed most people’s answer would be a resounding “no”, but in discussion, I received the response “it seems to work.” What does that mean? If a school achieves great exam results, has it “worked” – surely not. Actually, come to think of it, this isn’t even about homework. It’s about what counts as having “worked” in a (primary) school.

A large part of my childhood was spent outside with my friends building tree-houses. We were on our own. We made plans together, managed our interactions outside of any structures that were created for us, dealt with the unexpected, set our rules, judged risks and managed our relationships without recourse to external authority. To me those were some of the most important lessons I learned in my early years. Obviously, I was lucky, I grew up in leafy Cambridge with abandoned gardens to play in and that’s not transferable to inner-city estates. However, recognition that these were invaluable experiences prompts me to ask- shouldn’t free, unstructured time with peers in relatively safe spaces be part of any childhood? Shouldn’t all children have the opportunity to experiment and find their own way of interacting with others? Schools may do a great job of teaching children to be polite and friendly to each other or “to make eye contact with people and greet visitors with a handshake” as the head of Thomas Jones school explains; but, whilst important, learning to play by social rules and norms is not the same as having the space to develop your own unique way of interacting with others. ‘Social adjusted-ness’ is not the same as ‘social fluency’.

Part of the reason I see a difference between ‘social adjusted-ness’ and ‘social fluency’ is because for me, the latter also involves uniqueness, self-definition and even eccentricity. In a childhood dominated by an 8.50am -3.15pm + two hours homework day, where is the space for the pursuit of individual interests and passions? I once asked the head of a (superb) KIPP-style school, “what if one of your pupils was an amazing athlete and wanted to train to compete?” He was stumped- “it probably wouldn’t be the right school for them”. What a pity. Shouldn’t we be nurturing pupils’ unique passions, talents and interests? To return to my own (very lucky childhood): as a kid, I was learning the piano, the recorder(s), the trumpet and for a few years I decided I fancied learning Modern Greek (both my parents were linguists and so I wanted my own language). Others in my class had a passion for swimming and trained four times a week after school. All these things became part of who we were. They shaped our identity and moved us towards being unique adults. There’s hardly much space for that sort of thing if by the time you’ve got home, done your homework and perhaps had something to eat it’s around 6.30. And you’re a primary school kid. Sure- I was lucky to have music lessons etc., but if we’re to avoid the “soft bigotry of low expectations” and to give disadvantaged pupils even half the opportunities their more privileged (and high achieving peers) have access to, we shouldn’t be writing them out of these opportunities in some sort of deficit model that’s satisfied with looking to SATs results and concluding “it worked”.

So where does this leave parents and the family as a whole? One of the reasons I support giving a little homework to pupils, (even from reception age), is because it creates a link between school and parents. But two hours? If we want homework to be a bridge between school and parents then parents need to be around when it’s being done. If working parents get home at, say, 6 o’clock (lucky them) – assuming their kids get straight down to work on Mummy and Daddy’s arrival, then they should be done 8. Great for the rest of parents’ and children’s interactions eh?!

It could easily be objected that I’m arguing for a version of childhood far removed from the lives of the pupils served by schools like Thomas Jones. A lot of kids are unlikely to spend the time they would otherwise be doing their homework in building tree-houses, learning Greek and chatting to their parents about the today’s news. Their lives can be so chaotic and unstructured that schools need to counteract the shadow of enormous disadvantage. As someone who has spent plenty of time in high achieving, ‘no excuses’, inner-city turnaround schools, I am not one of those who looks at the Mossbourne’s of this world and sees joyless, results factories, oppressing individuality and churning out zombies. I am quite aware that structure and discipline can help pupils feel safe and so be liberating, allowing them to flourish in a way they could never have done otherwise. However, if we accept that developing social-fluency, uniqueness and relationships with parents are fundamental parts of childhood, then “what works” is not just what leads to outstanding SATs results. We need to look more broadly. How do we provide youth clubs that offer wider, less structured opportunities? The school I taught at had it’s own fantastic youth-club, staffed by teacher volunteers and giving pupils a safe space to have fun independently. At the primary school I am a governor of, we evaluate our success not only in terms of academic achievement and also our four values: “Unique”, “Boundless”, “Curious” and “Playful”.

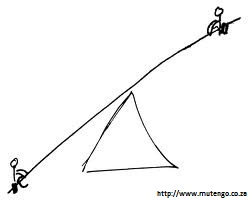

My fear is that current accountability measures have a distortive impact. It’s too easy to claim success for a policy just because it boosts exam attainment and/or progress. I’ve often used the analogy of a seesaw. In the past, schools balanced the need to prove success quantitatively through league tables, with the need to do well in an Ofsted framework that leaned heavily towards Every Child Matters. This second component has now been downgraded to such an extent that I fear schools will think policies “work” simply because there is an insufficient counterbalance to exam based measures.

Comments