London Schools Now we have a full(er) picture…

27th June 2014

We argue that London’s schools exist in a particular context and that this has shaped improvement but does not fully explain it. Instead, we conclude that the barriers to success like recruitment and funding which impeded school improvement in the 1990s were systematically tackled. Once these were reduced, excellence was secured by creating a sense of collective moral purpose and possibility through outstanding, data-driven leadership at every level (whether in Local Authorities, academy chains, by system leaders – like Sue John and George Berwick, or within central government and the London Challenge team – amongst people like Tim Brighouse, Jon Coles and David Woods.)

Pulling these two studies together gives us the best opportunity yet to understand the remarkable success of London’s schools but how do the two studies fit together?

The role of primary schools

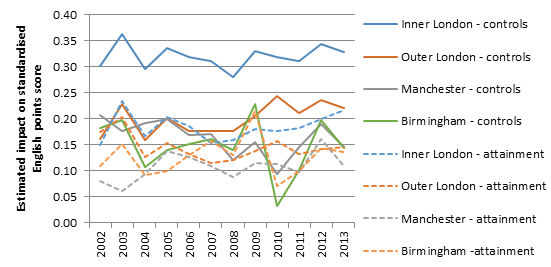

Monday’s IFS report showed that a large proportion of ‘the London advantage’ in GCSE performance could be explained by prior attainment at primary school level and highlighted London’s achievement in English at Key Stage 2:

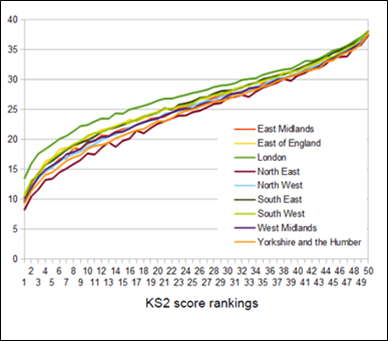

Figure A7 Estimated effect of being in London or other large cities on average standardised KS2 English points score amongst pupils eligible for FSM, with controls and with controls for KS1 teacher assessments: IFS/SMCP – Greaves et al. 2014

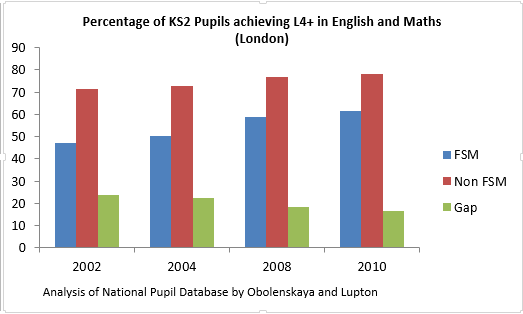

This was also clear in data from Obolenskaya and Lupton which we explored as part of our research:

It was outside of IFS’ scope to look at the whole education system across the period of improvement, but given the sequence of events, the authors suggest the National Strategies may have played an important role. Despite primary schools being outside our scope, several of our interviewees made reference to primaries’ important role and the contribution made by the National Strategies. This was particularly notable in two of our six focus boroughs: Barking and Dagenham and Tower Hamlets.

“The reason Barking and Dagenham did well was because [name] and his colleagues had got on to the importance of improving literacy and numeracy earlier and they were doing it more systematically… we kind of tailored the program to let them keep doing what they were doing, so built from the National Numeracy and National Literacy projects” – Senior Policy Maker

“We focussed on the literacy and numeracy… So there was a huge investment in terms of professional development related to those things… we would decide which school needed the support most and… not just double, sometimes more than double the resource. So we had many more literacy consultants than other places and many more numeracy and that was a huge help” – Senior Educationalist and ex-Director of Education Services

The Secondary Advantage

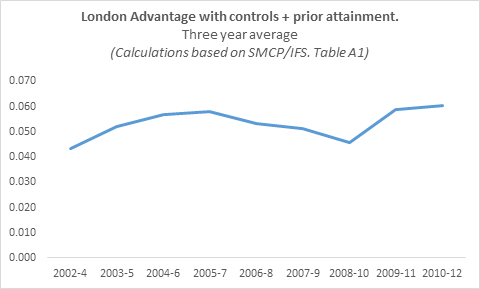

Yet this may not explain the full story. Although the IFS concluded that primary performance explained much of the London advantage, they found that even controlling for primary performance, a secondary school advantage remained.

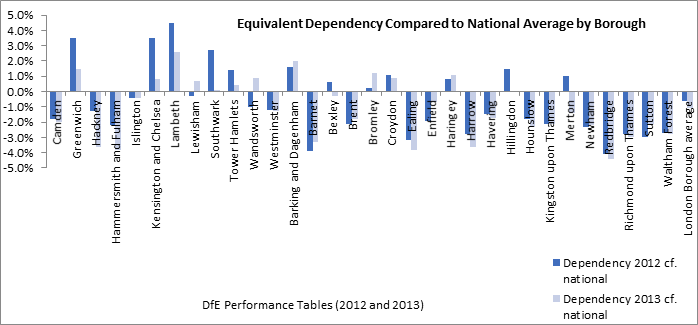

Furthermore, Chris Cook at the BBC has since argued that the IFS may have substantially under-estimated the size of the London effect at Secondary level since London schools have been less reliant on low quality ‘equivalent GCSEs’. This suggestion is certainly backed up by our work. We found that most London boroughs were less dependent on equivalents than the national average – something unexpected given that they disproportionately serve the disadvantaged pupils these qualifications are often targeted at:

The significance and consistency of the London secondary advantage is best illustrated in this graph from Chris Cook. It shows pupils’ GCSE performance by KS2 attainment excluding equivalents. It shows that regardless of their prior attainment, pupils in London’s Secondaries do better compared to pupils with similar KS2 attainment elsewhere.

London’s Secondaries therefore also have important strengths and some of these may be shared across both phases.

There is no one London story

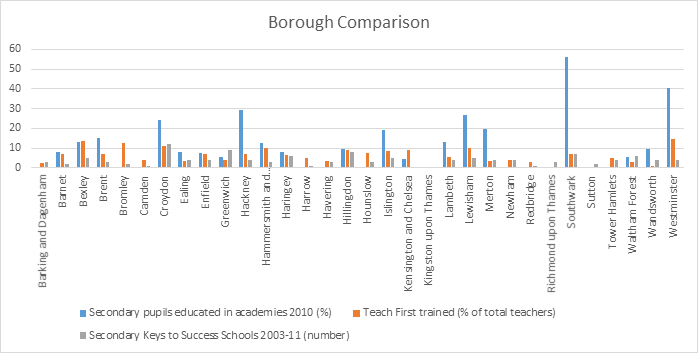

The IFS argue that programmes like academies, Teach First and London Challenge cannot explain London’s success because they were not prevalent in primary schools during the period of improvement. To some extent this is true. Similarly, we found no one London story when it came to these programmes: different boroughs had contrasting experiences and trajectories. No single programme or policy can claim credit for the improvement: some boroughs had many Teach First-ers, some had few or none; some opted for rapid academisation or outsourced their local authority, others drove improvement through their borough leadership; some had large numbers of Keys to Success schools (the most intensive London Challenge intervention) some none. Yet almost, (though not all), succeeded.

Cross cutting themes

My view is that four cross-cutting approaches featured in all these policies as well as amongst high performing local authorities and across the system as a whole. It is these that help explain London’s success:

1. Systematically dealing with barriers to success so that a minimum threshold was met:

Shortages of teachers were dealt with and re-advertising rates for school leaders dropped dramatically, inflated school deficits shrunk and dilapidated buildings were replaced.

|

Region |

Percentage change in the rate of Head Teacher appointments requiring re-advertising |

(1998/9-2000/01 average cf. 2008/9-2010/11 average) – Numbers averaged over three years to reduce impact of year to year fluctuations Inner London -25%Outer London +16%North East +78% North West +26% Yorkshire & Humber +66% East Midlands +68% West Midlands +64% East of England +43% South East +37% South West+5%

Howson and Sprigade, 2012

2. Objective challenge using sophisticated data:

Underperformance was robustly, fairly and objectively challenged using data that highlighted contextually similar schools and focused on progress as well as attainment.

London was ahead of the curve on this because expertise from ILEA (the Inner London Education Authority) moved into local authorities like Tower Hamlets and because London Challenge’s leaders promoted the use of contextually informed data – for example through ‘Families of Schools’.

3. Willingness to deal with persistent underperformance using ‘structural solutions’:

Where schools failed to improve, Local Authorities and central government were willing to take radical steps like federating or academising schools and outsourcing failing boroughs. This sent out strong signals that schools had no choice but to improve and removed the worst performers from the system.

4. Creating a London identity and a culture of collective mission built on teachers’ intrinsic sense of moral purpose:

A shared identity and a moral purpose was created and reinforced by using positive language about ‘London Schools’, ‘London Teachers’ and being ‘the best’. These were reinforced by programmes like Chartered London Teacher, Key Worker Housing and professional development opportunities, all of which were symbolically powerful. These changes were coupled with a new sense of possibility involving ambitious goals and school collaboration which illustrated what might be achieved. Whilst this sounds intangible, the contrast with the much maligned ‘national challenge’ could not be clearer.

These approaches were underpinned by London’s unique demographic context, the opportunities available and the city’s unusual borough-based political governance.

Our interviewees argued that it was these cross cutting principles that changed the culture of schools and that led to the outstanding teaching and leadership which ultimately transformed outcomes.

‘Lessons from London Schools: Investigating the Success’ is a Centre for London and CfBT report and we are grateful to both organisations for giving us the opportunity to carry out an in depth study of this crucial topic.

The views in this blog are my own and whilst my analysis is predominantly based on the IFS and CfL/CfBT reports, not all the data I have presented here are in either report.

Comments