This is the first in a series of blogs we will be publishing this week exploring some of the themes to emerge from our Centre for London/CfBT Report, Lessons from London Schools

London is not just a city, it is a region divided into 33 boroughs. Every borough has had a different school improvement trajectory and it is therefore a myth to talk about one London Story – as I explained in

my last post.In this post I go on to explain the contribution made by London’s borough structure and boroughs’ relationship to central government.

London’s borough structure seems to have contributed to London’s success in three main ways: Scale, pragmatism and competition/collaboration.

1. Scale

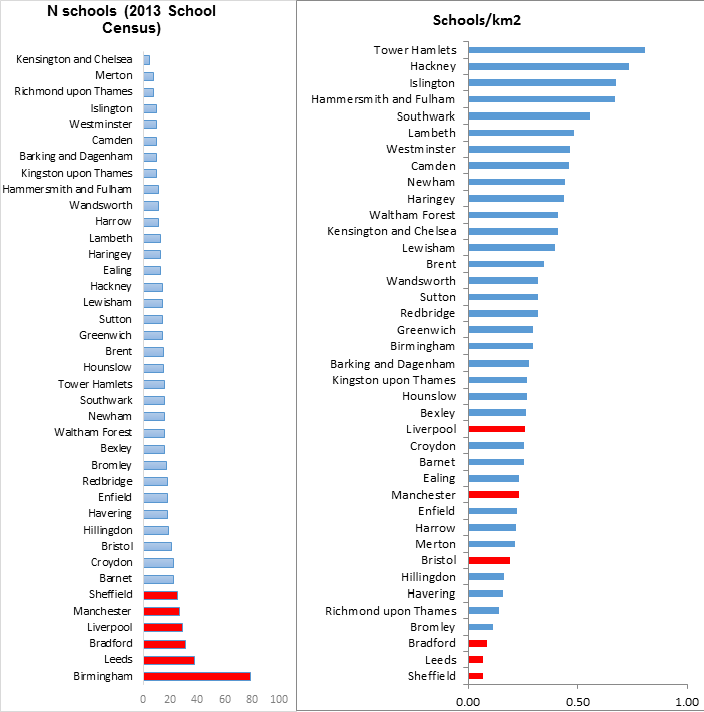

Even compared to other major cities London’s boroughs tend to have fewer schools concentrated in a smaller area – this contrast is even more extreme if one looks at the largely rural LAs that make up much of the country’s lower performing regions.

In interviews, Directors of Education and Children’s services in London repeatedly emphasised that their boroughs’ size influenced the way they worked. They argued they could have an ‘ear to the ground’ with regard to what was happening in ‘their’ schools. One explained:

‘You’ve got very small local authorities that are therefore able to have much more purchase, much more leverage, much more impact… The relationships that you can build up…I can get all the secondary heads around a table easily… they know that you will lie down in the road to support them, and… to be honest I don’t know how, whether…. if we were doing it in Kent or Cumbria, at that level of leadership, with the real authority, that I could walk into any governing body or work with any, to have that authority at that level I think the scale of London boroughs allowed that to happen.’

2. Local Pragmatism

The reason that boroughs pursued different approaches to school improvement was that decisions were made in response to contrasting contexts. In some cases this meant responding to a particular ethnic composition by engaging with a specific community – as the Local Authority did with mosques in Tower Hamlets. In others it meant whole-sale academisation or outsourcing where problems seemed intractable – as was the case in Hackney. London’s borough structure was helpful because it meant specific issues could be identified and tackled at a local level.

One ex-senior civil servant explained it would not have worked to take what happened in Hackney and drop it directly into Islington. This is something that should be born in mind when attempting to replicate success in different cities and regions.

3. Competition and Collaboration

Around 50% of London Heads in

Merryn Hutchings’ 2012 survey (

p36) had found working with schools outside of their LA particularly helpful. As one ex-advisor argued, London’s structure may have made for “the perfect balance of competition and collaboration”:

‘It’s big enough that you can run something like London Challenge, and you can find schools to work with other schools, and that they don’t feel particularly threatened by it because they are far enough away. But, they’re also competing with the schools near them, so you’ve got that… drive to be successful, because if you’re not successful you’ll look bad in comparison with the people around you, but at the same time, plenty of support from other professionals.’

One ex- Head explained why cross borough links made collaboration easier and helped overcome competition:

‘It’s often better to broker in someone from outside of the local authority because it’s just much easier for that person to gain the trust and gain entry, because they’re not seen as part of a local politics… they don’t necessarily want a local competitor being the person that’s working with them to help them sort out their problems. And there’s a bit of a pride issue. And secondly, there’s a bit of a kind of conflict of interest as well’

Whilst policy makers like to argue that competition and collaboration can co-exist, I have heard heads explicitly say they do not want to collaborate with local schools because they are in competition. Whilst London might be presented as proof that competition and collaboration can co-exist it is worth bearing in mind that the structure of the capital facilitated this. New regional and sub-regional improvement programmes will need to find solutions to this issue.

The Centre and the Local: A mutually reinforcing jigsaw

Mel Ainscow summarised the role of Local Authorities in Manchester as follows:

- Knowing ‘the big picture about what is happening in their communities’

- Identifying priorities for action

- Brokering collaboration.

- ‘Moving away from a command and control perspective’

- ‘Enabling and facilitating collaborative action across the city region’

London’s regional identity helped draw these functions together around the shared mission of making education in London ‘the best in the world.’

Meanwhile the centre provided:

- The engine for urgency

- A secretariat that provided the infrastructure for collaboration (for example dealing with admin and putting together families of school data)

- An advocate/sponsor that brought in the necessary resources (for example securing the London pay scale and setting up an over-all Leadership Strategy and Student Pledge).

On top of that, the centre was not afraid to step in when Local Authorities were unable to deliver improvements on their own: Challenge Advisors, sometimes in partnership with the LA, were therefore proactive in driving improvement in some boroughs.

The challenge to replication

The structures described in this blog facilitated success but were never sufficient conditions for improvement. I also don’t think they were necessary conditions: Whilst they were integral to London’s particular school improvement journey other approaches were possible – as Manchester and the Black Country revealed.

Given that other regions do not have the same structures as London, they should not try and replicate London’s approach wholesale and will need to adapt. Otherwise structural differences could prove barriers to success:

- We cannot expect each ‘Challenge’ to get its own Schools Commissioner or Minister to drive forward improvement – but leadership will need to come from somewhere.

- Geography may require the creation of small local clusters of schools- yet this may make overcoming competition harder.

My

four key lessons from London are therefore focused on ‘approaches’ to improvement, rather than particular mechanisms. Hopefully these will be less vulnerable to structural challenges.

‘Lessons from London Schools: Investigating the Success’ is a Centre for London and CfBT report and we are grateful to both organisations for giving us the opportunity to carry out an in depth study of this crucial topic.

The views in this blog are my own and whilst my analysis is predominantly based on the CfL/CfBT reports, not all the data I have presented here is necessarily in the report.

Comments