The coastal question: Ofsted and the new frontiers in education research

11th November 2014

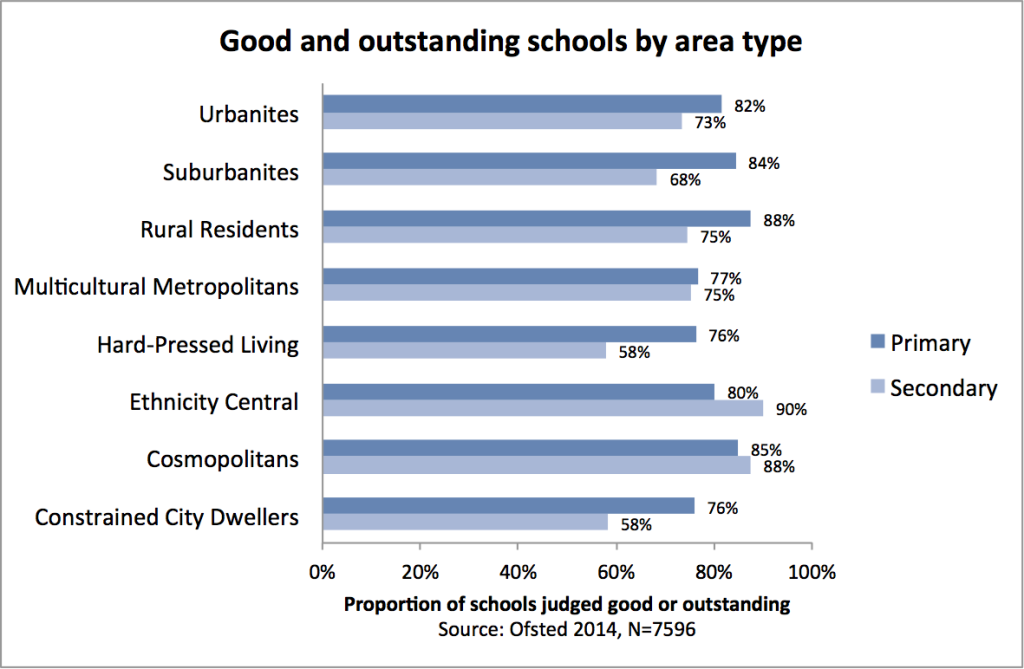

New data reveals that whilst 90% of Secondary schools serving areas classified as “ethnicity central” are graded good or outstanding, this figure is as low as 58% in areas classified as “hard pressed living” and “constrained city dwellers”.

It’s not news that our state education system produces different results in different parts of the country. Regional disparities in performance have been thrown under the spotlight by London’s ten year transformation, while the various city and regional challenges have an explicit geographical focus, and area-level deprivation remains the go-to indicator for organisations who want to work with challenging schools.

However, a new type of area-based disparity is climbing steadily up the agenda as bodies from Ofsted to Teach First turn their attention to the coastal and rural context. As Ofsted’s 2013 Access and Achievement report argued, “the areas where the most disadvantaged children are being let down… are no longer deprived inner city areas, instead the focus has shifted to deprived coastal towns and rural, less populous regions of the country.” This represents a subtle shift: away from the giant scale of regions to something more localised; away from ‘deprived and less deprived’ in favour of a definition that’s more contextual. It also begs the question: what data can we use to identify and explore these new contexts?

The ONS recently released its latest Output Area Classification which, when brought together with existing data from Ofsted, reveals that school performance varies considerably across different types of area, regardless of deprivation. Areas commonly found in deprived inner city locations fare well; more peripheral locations, often not notable for their deprivation, have schools that perform far worse – particularly at secondary. What’s exciting about the ONS data is that it reveals, in fine grain, exactly where these underperforming areas are, and by looking at the Census data underpinning these area types we can begin to unpick the specific factors that lead to their poor school performance.

Rather than defining areas as simply more or less deprived, the Output Area Classification defines a given area as belonging to one of eight different ‘area types’, based on a host of Census data – from the age of residents, to the types of homes they live in, to the types of jobs they do. The real power of this area typology is that it distinguishes between deprived central London and the deprived fringes of Southampton; between the affluent suburbs of south Manchester and the affluent villages of the home counties. OAC’s eight main area types range from Cosmopolitans and Ethnicity Central, which cover the vast majority of London’s spatial area, to Constrained City Dwellers and Hard-Pressed Households which constitute a large proportion of places like Basildon, Plymouth and Sunderland. Cosmopolitan areas of central London and Hard-Pressed areas of coastal cities may share very similar levels of deprivation, but they have different Census characteristics. While the former are defined by high proportions of full-time students and people working in information and communication, the latter are defined by lower levels of qualifications and lower proportions of non-White residents. OAC distinguishes between these places in a way that regional and deprivation-based approaches do not.

The point is not that all coastal towns and cities are uniform, but that many coastal settings share a similar OAC composition. And the value of OAC is its ability to pin down, in terms of precise Census characteristics, how deprived inner city contexts from London to Leicester differ so markedly from deprived coastal and rural contexts, from Tyneside to Torpoint. In turn, by exploring the performance of schools and pupils in different types of area, we can begin to identify the particular contexts where educational outcomes are weakest.

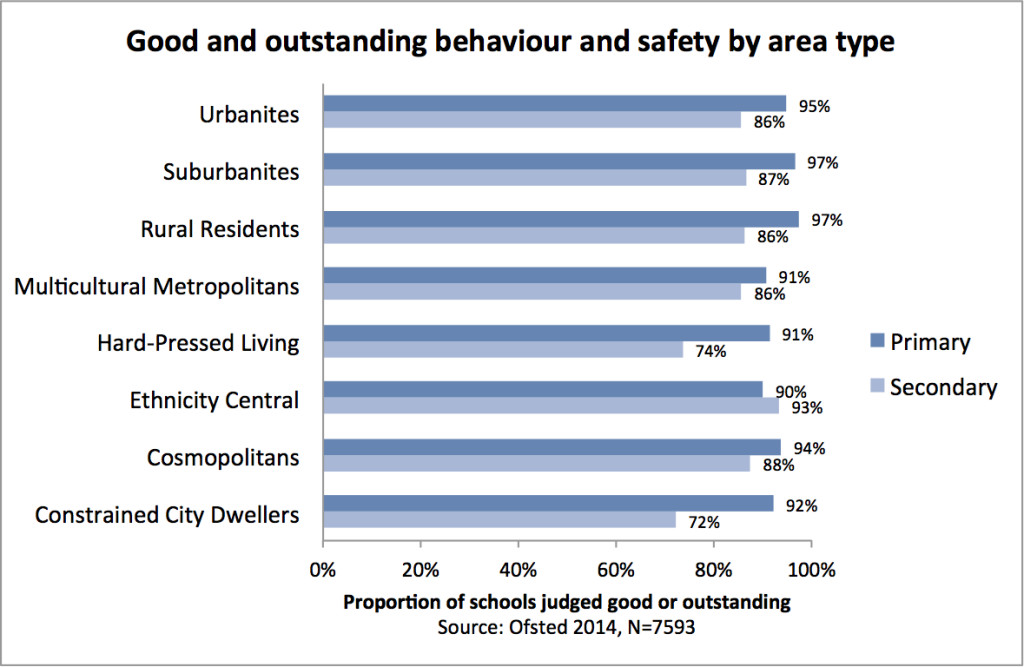

Merging OAC data with Ofsted’s latest official statistics reveals stark differences in school performance in different types of area. In areas defined as Ethnicity Central 80% of maintained primary schools have a good or outstanding judgement, rising to 90% of secondary schools. In comparison, in areas defined as Hard-Pressed Living 76% of primary schools and just 58% of secondaries are judged good or outstanding. In fact, on all aspects of Ofsted’s evaluation schedule, from teaching quality to leadership and management to behaviour and safety – cosmopolitan, multicultural and ethnically diverse areas have secondary schools that are rated similarly well, or better, than their primary schools. Hard-Pressed and Constrained City Dwellers area types, meanwhile, start from a lower base at primary which erodes further at secondary.

This basic analysis of school performance by area type generates two insights. Firstly, school performance varies markedly between different types of area, regardless of deprivation. Secondly, school performance appears to be weakest in the types of area that define many coastal and rural areas, but these area types are also found at the edges of the capital and the urban core of many provincial cities. It’s a welcome development that we are turning our attention to coastal and rural areas, but this ‘coastal and rural’ focus arguably doesn’t do justice to the nuanced range of areas where our education system is underperforming.

Comments