White Lightning and happy teenagers- the standards and well-being conundrum

9th January 2015

“Given the improvements in behaviour; the reduction in criminality; the falls in truancy; the increase in aspiration; the improvements in home lives – all of which are known to link to academic attainment – why haven’t we seen a commensurate, observable, rise in academic standards?”

At LKMco we have broken Sam’s puzzle into three separate questions, and this blog is the first in a three part series that asks:

• are children really getting more sensible and happier?

• have standards really stagnated?

• if Sam’s premises are correct, why haven’t standards improved?

Are children really getting more sensible/happier?

Sam uses various datasets to show that there have been improvements in a range of “non-cognitive”measures such as trying drugs and alcohol, being aspirational, going to University, etc. In doing so he paints a picture of a happy, sensible cohort of young people, who clearly ought to be doing better at school. However in this blog I will argue that other statistics paint a less rosy picture, and that furthermore, teenagers may just be finding new ways of rebelling.

At first glance, recent survey data, alongside headlines from Children’s Society and UN reports, seem to support Sam’s conclusion. However dig a little deeper and you soon find evidence to suggest that our children are not quite so sensible, nor happy with their lives, particularly in a school context. This may go some way to explaining the apparent disconnect Sam identifies.

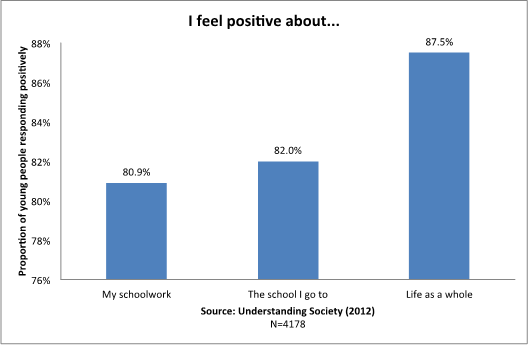

The latest data from the Understanding Society survey indicate that around 8 in 10 young people aged 10-15 feel positive about their schoolwork and the school they go to, while almost 9 in 10 feel positive about life as a whole.

The UN’s 2013 Innocenti Report Card 11, looks at child wellbeing in rich countries, and places the UK 16th out of the 29 countries it examines (having risen from 21st out of 21 countries in 2001). It places us 15th in terms of risk taking behaviour but 24th in terms of educational outcomes for young people – data which seems at first glance to support Sam’s premises – our children are taking fewer risks, but this isn’t translating to better academic achievement. The report echoes Sam’s data on drugs and alcohol use, showing that we have pretty low rates comparatively. However it also shows that almost 30% of children have been bullied in the past couple of months, and over 35% of children have been involved in fighting in the last 12 months. Sam argues that bullying has declined, but the decline shown in the DfE data he references is only of 5 percentage points, so rates still remain high. It’s unlikely that children being regularly exposed to bullying and/or violence are making the most of the educational opportunities their school is providing.

The Children’s Society found that 90% of children in England consider themselves to have relatively good wellbeing (depressingly, this still puts us 30th out of the 39 countries they compare). However the report picks out a number of issues that are worrying young people – including their appearance, their future and school.

This raises the question of whether there are new, different forms of risky behaviour that our surveys simply aren’t asking teenagers about yet. Teenagers are well known for finding new ways to break rules and taboos. Perhaps the huge increase in technology and social media might mean that children are sitting at home comparing themselves to photoshopped images of models, posting inappropriate pictures on instagram, and giving their bank details to strangers on the internet. This probably isn’t any better for them than the copious amounts of White Lightning teenagers were drinking at bus stops ten years ago.

This more concerning narrative on the private lives and feelings of our young people is reinforced by the thoroughly depressing 2014 Youth Index from the Prince’s Trust. Their research asks young people not just what they’ve been up to, but also how they are feeling, and reveals some shockingly high levels of anxious children. 11% have been prescribed anti-depressants, 22% have had panic attacks, 19% have self harmed and 26% have felt suicidal. 36% of boys and 54% of girls have experienced “self loathing”. Sam argues that relationships with parents have improved, and that may well be the case, however from what starting point, and to what level? The Youth Index found that 58% of young people do not have a parent they consider a role model, and only 64% always or often feel loved – a truly heartbreaking statistic. Given this, is it any wonder they aren’t hitting the books with a huge amount of efficacy? Things might have improved, but also stayed well below the level needed to translate into success.

Ultimately, it might be that our young people are not quite as happy nor sensible as Sam’s datasets initially suggest.

In our next blog in this series, Meena asks whether standards have really stagnated…

Comments