The UKIP voters of tomorrow

19th May 2015

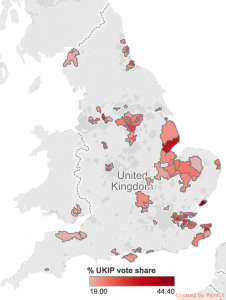

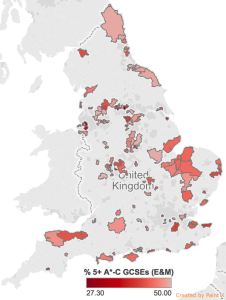

The 2015 General Election held a lot of surprises, not least the fact that almost 4 million people turned out to endorse UKIP. Although the party won just a single seat, support for the far-right party was remarkably high, particularly in the more disadvantaged areas of the country. Sam Freedman suggested that the geographical distribution of UKIP popularity seemed very similar to that of educational under-performance. He’s right – the map is almost identical. It is time to wake up to the uncanny relationship between UKIP voting and education.

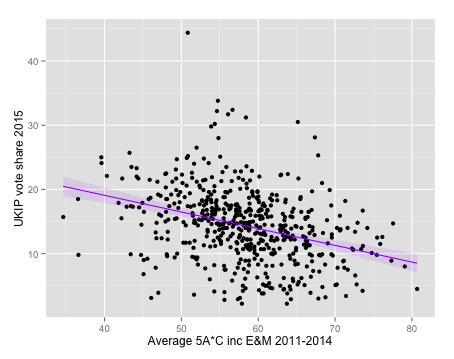

The fact that UKIP received its largest endorsements in areas where school performance was especially low wasn’t a surprise to Tim Wigmore who hypothesised, “The links between failing schools and UKIP may run deeper”. And run deeper they do. My analyses of vote share and educational data from the 533 English constituencies show that areas with higher UKIP vote shares tend to have lower average GCSE performance.

Whilst there are some outliers, the negative relationship between areas of educational underperformance and UKIP voting is undeniable. It is also quite strong (r = – 0.34) with every quarter of a per cent reduction in average GCSE performance significantly associated with a rise in local UKIP vote share by 1 per cent.

However, links between educational performance and party vote share are not limited to UKIP. Areas where the Conservatives command a large share of votes are quite different, typically doing very well educationally. The equivalent relationship is positive (r = + 0.38), with every three quarter of a per cent increase in average GCSE performance significantly associated with a 1 per cent rise in Conservative vote share. And it’s not just for the GCSE measure – the patterns demonstrated here can be repeated when looking at other educational outcomes, such as the percentage of children achieving the EBacc or the percentage of pupils in schools that are deemed to “require improvement” or be “inadequate”.

It’s important to note that this relationship may not be causal. Dissatisfaction with low educational performance is just one of many factors that could have persuaded people to vote for UKIP. Whilst policies such as UKIP’s proposal to reintroduce grammar schools may have played a role, a third variable could well be causing both low educational performance and high UKIP vote share. For example, high levels of deprivation and unemployment, and low levels of parental education could cause both low educational performance and high UKIP vote share.

Political scientists, Rob Ford and Matthew Goodwin, first highlighted the connection between UKIP support and low educational attainment in their 2014 book, Revolt on the Right. Given the strong relationship between parents’ educational attainment and that of their children, it is a worrying phenomenon that just 13 per cent of UKIP supporters have a university degree, whilst over half left school at 16. The children of UKIP supporters are doubly disadvantaged: not only are they more likely to come from educationally disadvantaged backgrounds but they are also more likely to attend some of the worst performing schools in the country.

Whatever the causes of the relationship between education and UKIP voting, it is clear that we cannot continue to ignore areas of the UK where educational performance is low, and where voters feel endorsing UKIP is the best way to improve things for themselves. Without major educational and economic interventions in disadvantaged areas, children struggling in low performing schools today could “end up becoming the UKIP voters of tomorrow”.

Comments