How big’s your slice of the cake? The National Funding Formula

17th March 2017

On a cold Wednesday morning last year, when teaching physics in an academy in Hackney, I felt the first, chill winds of the cuts to school budgets that have been widely reported in the press and starkly mapped out in today’s Education Policy Institute Report on the National Funding Formula (NFF).

The staff were gathered in the foyer to listen to the head’s briefing.

“I’ve got some bad news,” he said, looking grave. “Budgets are being slashed, left, right and centre, and I’m afraid we’ve had to take immediate action.”

What’s next? I wondered. Bans on buying equipment? Salary freezes? Job losses?

“From Monday, the coffee machine will only be available until break. It will then be switched off to save money.”

Gasps spread like a contagion. Humanities were almost in tears. The full implications were only just sinking in: no flat whites after 10:50. I felt numb.

Redistribution?

Clearly I’m exaggerating. However, while budget cuts will undoubtedly have a profound impact on pupils, Hackney was highlighted by Education Secretary Justine Greening as an unfair beneficiary of the current funding system. According to her, its schools currently receive 50% more money per pupil than those with equivalent levels of deprivation in Barnsley. It certainly seems strange that while we were worrying about where our next cappuccino would come from, heads in Barnsley were having to cut back on teachers.

Greening argues that a new National Funding Formula (NFF) is necessary to address this imbalance. Her opponents, including many in her own party, maintain that the current changes will put major pressures on schools. Who’s right? Well, both of them.

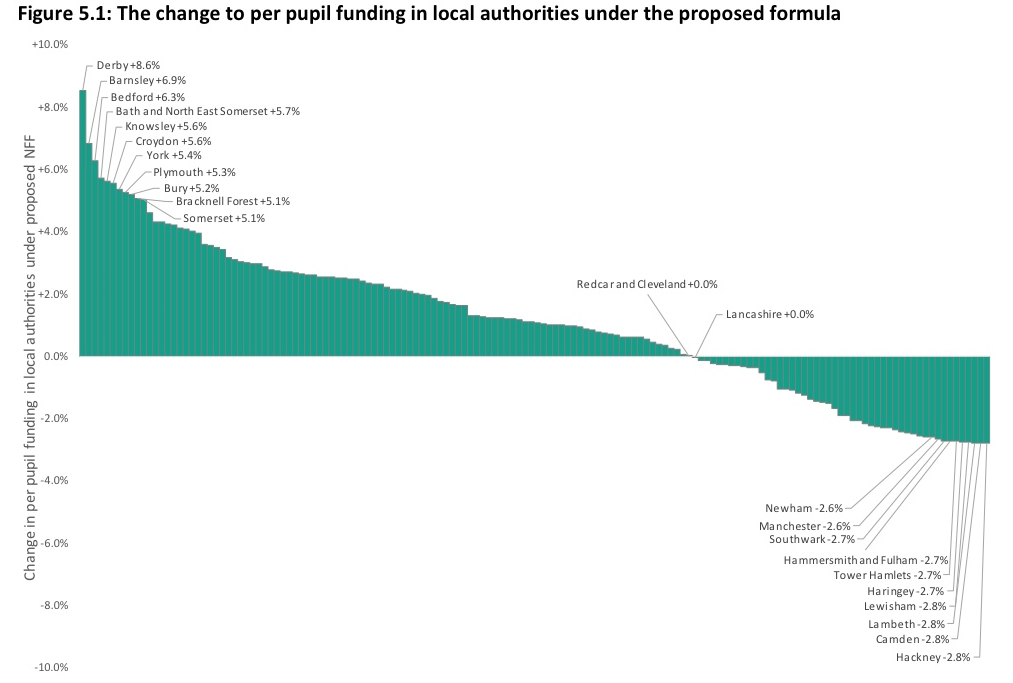

Distribution of cuts and gains under the NFF (EPI 2017)

Twin processes

There are two processes going on here: cuts that will affect how much cash is available to schools, and the NFF which determines how the cash is distributed. Like EPI, I’d argue that funding reforms are needed, and that it’s overall cuts that are responsible for much of the present angst – not the formula. To illustrate the distinction, it’s worth taking a quick tour of the recent history of funding policy.

A contentious history

The idea of a centrally-determined funding formula is nothing new. Even before New Labour came to power in 1997, the then Shadow Education Secretary David Blunkett warned that the Tories were planning to make such a proposal. 10 years later, it was his own government that introduced the Dedicated Schools Grant (DSG). Some saw this more systematic allocation of funding as the first step towards the type of formula Labour argued against in opposition. Finally, coalition Education Secretary Michael Gove proposed the NFF in its latest incarnation soon after Labour left office in 2010.

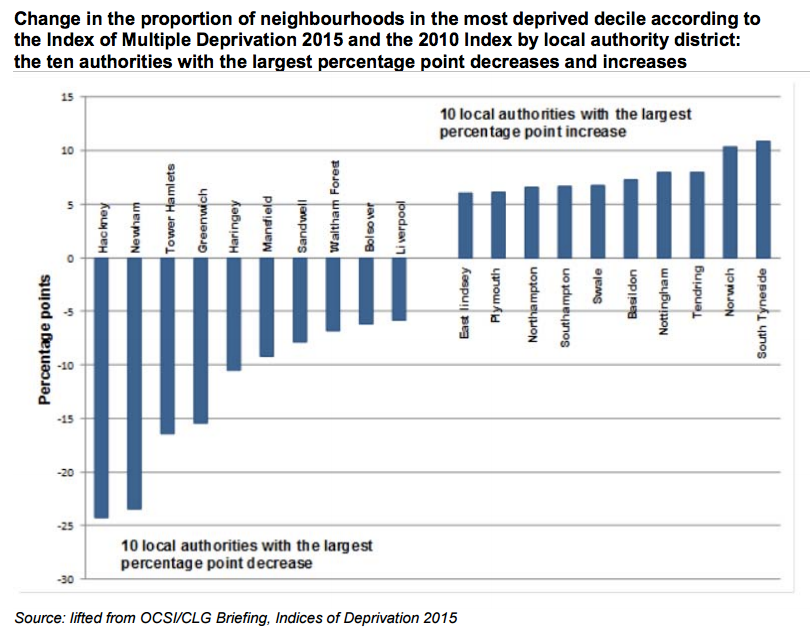

Advocates of the NFF argue that the current system does not reflect present needs because it awards funding based on the relatively arbitrary baseline of 2005-2006, the year before the DSG was introduced. Hence Hackney, a borough which has changed more than any other in recent years in terms of deprivation (see below) and educational outcomes, is still being funded as if it were the basket case it used to be.

The current proposals

The NFF aims to correct historic imbalances by redistributing resources to the schools most in need today. The current proposal is for this to be based on 11 factors including prior attainment, sparsity of schools and local business rates. There are also smaller ‘blocks’ of funding for high needs and early years, which are being consulted over separately.

This approach would appear to make sense. Surely it’s only right that boroughs like Hackney, which have benefited enormously from the extra funding they’ve received during the past 10 years, to take a step back to allow those with greater present needs to fill their bowls?

This however isn’t how the NUT sees it. They argue that the NFF is actually nothing more than a smokescreen for government cuts, not just in Hackney but across the country as well.

“Sufficiency”

Is this fair? To a certain extent. Unless the government puts more money on the table, school budgets will need to come down by around 8% by 2020 overall. As the EPI report points out, this could result in secondary schools losing an average of nearly £300,000 per year, or around six teachers – something that Greening has been far less keen to talk about. However, to blame the NFF for the cuts is to conflate two very different issues. The NFF determines how the cake is sliced up; cuts determine the size of the cake overall.

Today’s report highlights some important concerns about which schools get which slices but the most alarming figures are a consequence of rapidly shrinking cake. They therefore form part of a much wider debate about how much the UK as a nation is willing to pay for its public services.

This is the crux of the argument. MPs representing constituencies like Hackney were always unlikely to vote for the NFF because of its likely effects on local schools. On its own this might have been manageable, but in tandem with cuts it means a smaller slice of a smaller cake. This represents a double blow which may prove too painful to bear. The current situation, in which certain boroughs’ financial concerns are of an altogether frothier nature than others’, therefore looks set to continue.

Is it fair that proposals for a more equitable distribution of funding risk being thwarted by political pressure? Not really. Schools across the country are going to be hit by cuts, but those which were in need in 2005 will still receive more funding than many that are in need today if the NFF fails.

Today’s report suggests that the NFF needs tweaking, not scrapping. However the success of the whole enterprise may depend on Justine Greening persuading the treasury to cough up the £3bn that schools are said to be short of. Ultimately, fair funding may mean accepting that we need to spend a whole lot more on education. Or as the EPI put it more politicly: “a bottom-up costing might not be consistent with a politically realistic quantum of funding”.

Comments