Schools are not the only front in the battle for equality: Challenge the Impossible

1st March 2017

Commenting on our latest Social Mobility Commission Report, Jack Marwood argued that it should come as no surprise that schools aren’t able to reverse all the disadvantage that poverty brings.

Does this really surprise anyone? Should we really expect schools to reverse this? Given this, should Ofsted criticise individual schools?

— Richard Selfridge (@Databusting) February 27, 2017

He is right of course. And hopefully, by highlighting the range of challenges pupils and families face, our report casts light on the range of support that is needed. A new report from Teach First today also helps by showing that schools can’t do everything – it makes it clear they are only one front in the fight for equality.

Teach First’s report explores what happens to disadvantaged students at university and once they transition into the labour market. In stark terms, the report reveals the long running impact of poverty, even when pupils have overcome the odds at school. This is important because there are plenty of people who think that so long as schools do their magic, everything will be OK. According to this view “good schools = equality of opportunity”, and thus we needn’t worry too much about equality of outcomes.

What happens at uni?

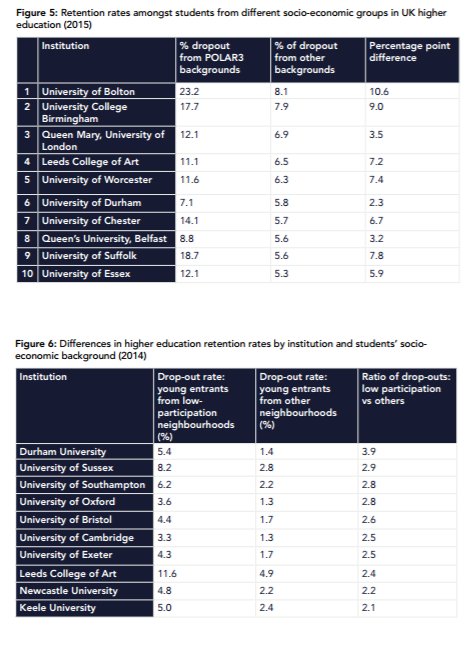

However, as we have shown in our previous research, university drop-out rates vary widely.

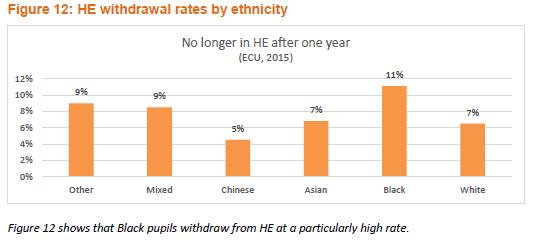

Today’s report confirms that there are worrying trends in university dropout rates by comparing retention of students with different socio-economic statuses (SES).

Of course, schools could perhaps do more to prepare pupils for university to avoid this, but the burden needs to be shared. Schools can’t do everything.

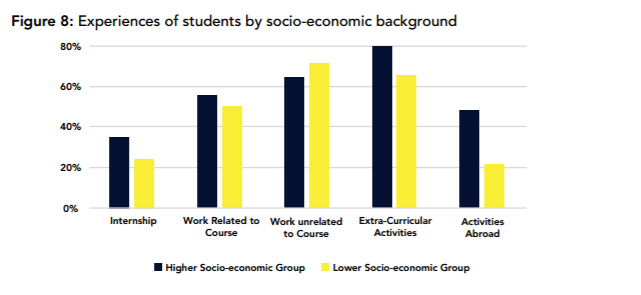

The report also shows that economic inequality has a huge impact on students’ experiences at university. SES affects whether students have to undertake part time work, their ability to participate in internships and their chances of travelling abroad.

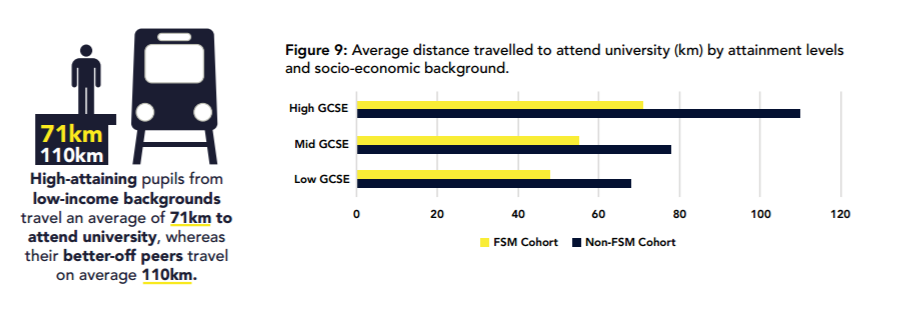

Furthermore, practical constraints like travel distance (which may also be linked to willingness to accept distance from family and community) also affect which university young people from different socio-economic groups attend.

What happens in the labour market?

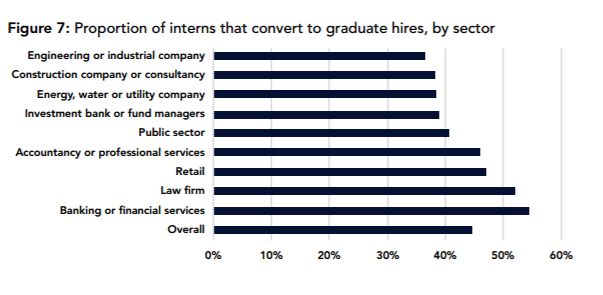

Given the role of internships in labour market transitions the stats on participation in internships (above) are a serious cause for concern.

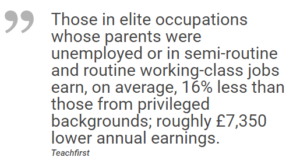

The report concludes by showing that even those who make it into elite jobs earn less, despite their ‘against all odds’ success.

The report concludes by showing that even those who make it into elite jobs earn less, despite their ‘against all odds’ success.

Given these striking stats, it is clear that it is not just better schools that are needed for all young people, regardless of background to make a fulfilling transition to adulthood. Schools can and should do a lot; but let’s not pretend that it’s OK to leave everything to them.

Comments