UTCs: Who’s Going and Why Should We Care?

12th July 2017

The Baker Dearing Trust’s call for University Technical Colleges to recruit ‘best-fit’ pupils has rightly been criticised for promoting selection. However, formally sanctioned selection is not the only form of pupil sorting. Recent research demonstrates the need to examine UTC’s existing, albeit organic, pupil selection and how this impacts on outcomes.

The UTC model, in itself, separates young people by offering some 14-19 year olds an alternative curriculum. In their guidance, the Department for Education explain that UTCs are legally academies which focus on subjects that require “modern, technical, industry-standard equipment” alongside a “broad, general education.” Furthermore, UTC’s entry age heightens their exclusivity as it is not commonplace for 14-year-olds to change institutions. Therefore, only some pupils leave their secondary school to focus on technical skills, whilst the majority remain and follow a mainstream curriculum (you can read further concerns about UTC’s entry age here).

Recent research shows that certain characteristics make pupils more or less likely to attend a UTC, suggesting that UTC pupil recruitment does include an element of organic selectivity. Although the NFER’s recent report concluded that proportions of UTC pupils on Free School Meals are broadly representative of surrounding areas, the report found concerning trends for UTC pupils:

- 70% are male, although there has been a slight year-on-year increase in the proportion of females.

- A higher proportion of pupils have special educational needs, compared to wider local authorities in which UTCs are located.

- UTC Pupils had higher absence rates during KS3, compared to non-UTC pupils. This continues at KS4, suggesting that UTC pupils may be those who are less engaged in the early years of secondary school.

- Pupils with higher KS2 attainment are less likely to go to UTCs.

Furthermore, pupils with higher KS2 attainment are less likely to attend a secondary school which acts as feeder for UTCs. This is worrying as it suggests that a select group of young people are encouraged to attend UTCs, few of these being from schools with high KS2 prior attainment. Whilst some argue that offering an alternative form of education to lower attainers may help to re-engage them, this is not the officially stated rationale for UTCs. What’s more, if we pigeon-hole pupils based on their characteristics at such a young age, we limit opportunities for all.

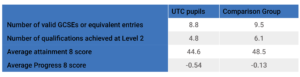

Things don’t get brighter when we take a look at UTC’s KS4 data. On average, pupils who attend UTCs take fewer GCSEs and make poorer progress compared to non-UTC pupils with similar starting points.

NFER, 2017

As the NFER explain, we cannot attribute this data solely to UTCs as they do not educate pupils for the full 5 years of secondary school and headline measures may not be the most effective way of assessing UTC’s success in teaching technical skills. However, the picture is still concerning. Do we have high enough expectations of pupils in UTCs? Or is society pushing the stereotype that those who have school engagement issues, including attendance, should go to a different institution and not bother with academic GCSEs?

A study by Ross et al suggests that learning vocational subjects does not help to re-engage Year 10 pupils. Furthermore, in 2014, the NFER found that only 25% of parents judged vocational education as worthwhile. These findings worry me. If problematic stereotypes about UTCs prove to be prevalent, these institutions risk being organically selective to the detriment of pupils.

Ways forward

- In 2016, the government introduced legislation requiring schools to work with learning providers to make Year 9 pupils aware of 14-19 educational routes. This year, legislation was also passed to ensure that schools give 13-18 year olds access to a range of education and training providers. As the NFER explain, we will not know the impact of these requirements until at least the 2017/18 academic year. To ensure that UTCs have truly inclusive cohorts, the impact of these reforms must be monitored closely.

- UTCs, other schools and society as a whole should have high expectations for UTC pupils. Rosenthal and Jacobson’s infamous study demonstrates that high expectations result in better pupil attainment. UTC Reading, the first UTC to be graded as Outstanding, was commended for teachers’ high expectations of all pupils. However, in 2016, Sir Michael Wilshaw cited low expectations as a common weakness in poorer performing UTCs.

- To effectively understand outcomes for UTC pupils, further research on pupil destinations is needed. Policies and practices should be adjusted in accordance.

As Anna Trethewey discussed in relation to the grammar school debate, selection limits some young people’s educational opportunities. Low expectations exacerbate barriers. To avoid a two-tier system and to provide equal opportunities, we must raise expectations for UTC pupils.

Comments