The Difference: Pupil Exclusion and Alternative Provision

10th October 2017

Classroom teachers should not be alone and unsupported in making the difference to pupils at risk of exclusion.

A new report is out today, launching “The Difference”, a new programme to place mainstream teachers in Alternative Provision where they will receive support and development so they can better support the most vulnerable young people in our schools.

It is welcome news. Unfortunately, things have not yet improved since we published our 2015 report, “The Alternative Should Not be Inferior”. Indeed things have got worse. Given spiralling mental health problems and ever greater pressure for schools to boost their results combined with a dearth of the necessary support and expertise, this is hardly surprising.

Five main reasons why this programme could make a difference

- Visibility: Like Special Schools, Alternative Provision is the Cinderella sector.

When I started work on our 2015 report I hardly knew what Alternative Provision meant, despite having worked in a school which excluded far more pupils than I like to even contemplate. If more people understood the sector it would attract far more attention, potentially making it easier to recruit for and share good practice. This would be welcome news given the large number of unqualified or supply teachers working in the sector.

When I started work on our 2015 report I hardly knew what Alternative Provision meant, despite having worked in a school which excluded far more pupils than I like to even contemplate. If more people understood the sector it would attract far more attention, potentially making it easier to recruit for and share good practice. This would be welcome news given the large number of unqualified or supply teachers working in the sector. - Reducing exclusion: Improved expertise within schools will mean more opportunities to respond to pupil needs before pupils are excluded. Alternative Provision is not always a bad thing for pupils as the report points out, but as we point out in ““The Alternative Should Not be Inferior” supporting vulnerable pupils within the mainstream is key too.

- Professional development and career pathways: Teachers want a range of career pathways, not everyone wants to be a head of department or head of teaching and learning. A specialist pathway, such as this, could open up more options and potentially be complementary to roles like pastoral leads and SENCOs.

- Improved collaboration: Schools cannot do it all alone. They need to work with other professionals but at the moment, too few professionals know how to do this. Today’s report points out that many referrals are poorly made or potentially unnecessary, resulting in one leader saying that ‘Social care and schools are basically at war’.

- Tackling critical shortages and skills gaps in AP: The sector is currently plagued by unfilled leadership posts and a shortage of permanent teachers. Whilst professional development in AP is, according to the report, rarely focused “on teaching, assessment or pedagogy; the most common training in AP schools covers ‘positive handling’ to reduce behaviour escalation, and safe ways to physically restrain pupils.” Anything that tackles this should be welcomed.

Key stats from the report

- Every cohort of permanently excluded pupils will go on to cost the state an extra £2.1 billion in education, health, benefits and criminal justice costs. Despite this, more pupils are being excluded, year on year.

- One in two leaders say their teachers cannot recognise mental ill health, and three in four say they cannot refer effectively to external services.

- Once a child is excluded, they are twice as likely to be taught by an unqualified teacher and twice as likely to have a supply teacher.

- Every day, 35 of the most disadvantaged children – equivalent to a full classroom of pupils – are permanently excluded from school, with disastrous personal and societal consequences. In fact, our research reveals that official figures significantly underestimate the actual number of children in this position.

- Only 1 per cent of excluded pupils get five good GCSEs. Among the sample in the longitudinal 2010 Youth Cohort Study, nearly 9 in 10 (87 per cent) young people who had never been excluded from school had achieved their level 2 qualification by the age of 20 (DfE 2011). By contrast, only 3 in 10 (30 per cent) excluded young people had achieved these qualifications by the same age.

- Children who have been taken into care are twice as likely to be excluded as those who have not (DfE 2017d). Moreover, ‘children in need’ – whose home lives have prompted interaction with social services but who remain in their home environment – fare even worse: they are three times more likely to be excluded from their school than other pupils.

- The majority of UK prisoners were excluded from school. A longitudinal study of prisoners found that 63 per cent of prisoners reported being temporarily excluded when at school (MoJ 2012).

- Among the top 20 local authorities for large PRU populations, there are several where quality of provision is particularly poor. In Gateshead, Barking and Dagenham, and Reading, 100 per cent of places for excluded pupils are in less than ‘Good’ provision.

Three remaining questions

I am certainly an enthusiast for the approach but have the following questions:

- According to the report “More than half of surveyed leaders said they would be interested in hiring The Difference leaders”. This is actually quite a low figure. Why is this and what needs to happen to make it change?

- Participants in the programme will be simultaneously taking their first leadership role and first foray into a new sector. This seems quite a lot to do at the same time and the moment when teachers are getting to know a new sector isn’t necessarily the time they are best placed to go straight into a leadership role. Admittedly recruits will need to have some whole-school or middle leadership training, but is this enough?

- I agree that schools should develop greater expertise in responding to pupils’ needs, however they cannot take on too much. Getting the balance between schools taking more responsibility themselves and working with others will be key. Teachers can’t be expected to do everything.

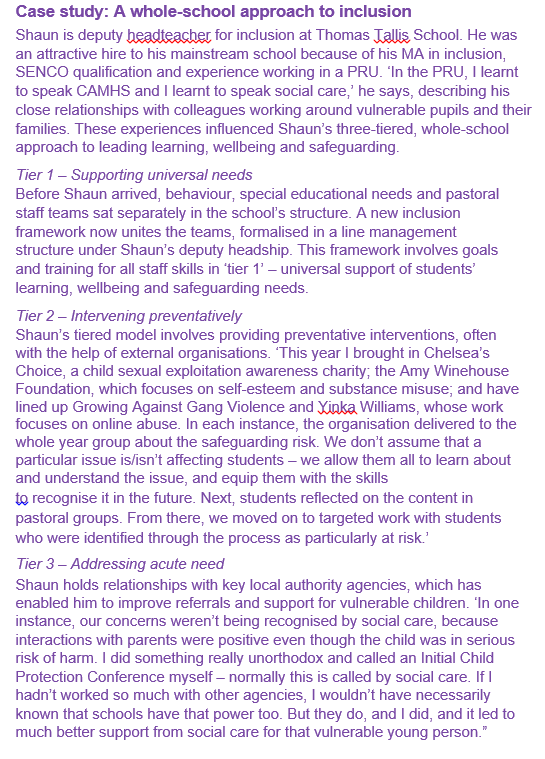

However reading the report’s final case study provides a useful insight into the programme’s full promise. As such, I look forward to seeing this programme become a real game changer for some of our most vulnerable students. We certainly can’t underestimate the urgency of tackling the issue.

Comments