Tackling Polarisation: Unpacking complexity in education debates

23rd July 2018

Unpacking Complexity

Two weeks ago, when the LKMco team sat down to consider what we wanted research at LKMco to do we agreed that:

“Polarisation in education rarely benefits anyone and instead want to shine a light on nuance and complexity to bring together those with different points of view and help them move on.”

Yet research shows that it is incredibly hard to generate positive discussion between people with opposing views. A new article by Amanda Ripley explores exactly this question and provides important lessons for those of us wanting to foster nuanced debate.

Intractable conflict

Ripley begins by pointing out that when faced with “intractable conflicts” (eg. “Should we exclude disruptive pupils”) we tend to enter a “hypervigilant state” in which we feel:

“an involuntary need to defend our side and attack the other. That anxiety renders us immune to new information.”

Ripley points out that in such a state “no amount of investigative reporting or leaked documents will change our mind, no matter what.”

The same could be said of research on controversial topics, yet if research on ‘intractable’ questions about education won’t impact on what people actually think or do, what’s the point?

Fortunately, Ripley goes on to highlight a number of approaches that can help ‘complicate the narrative’ such that a more fruitful debate ensues. To do so she draws on various studies and experiments that compare different types of conversations about polarising issues and which identify the characteristics of some of the more constructive discussions.

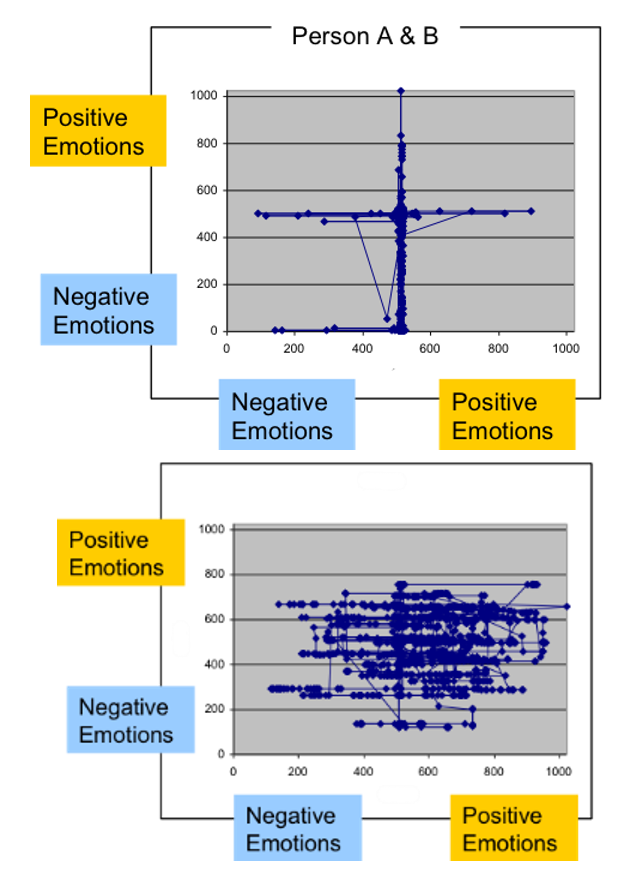

In these conversations, despite having negative feelings at times, tracking participants’ emotions shows a constant cycling between different feelings rather than it appearing ‘like a tug of war’.

This blog provides a short summary of her article and pulls out what the education and youth sector could learn from what she says.

Priming for complexity

The first experiment Ripley describes involved ‘priming’ conversation participants by getting them to read texts about a controversial issue, such as gun control, before they began their conversation. One group were presented with an article arguing a particular case, whilst the other read a piece unpacking the complexity, nuance and contradictions behind an issue. When participants went on to discuss an unrelated controversy, those who had read the second version went on to have more positive conversations in which they asked more questions. They were also more satisfied with their conversations and were willing to continue the discussion.

If we want to encourage constructive discussion about controversial topics in education, perhaps we need more blogs and articles forensically examining issues rather than arguing a case. As Ripley put it:

“Complexity is contagious… tidy narratives succumb to the urge to simplify, gently warping reality until one side looks good and the other looks evil… Complexity counters this craving, restoring the cracks and inconsistencies that had been air-brushed out of the picture.”

Complexity can also be drawn out of discussion and this is important to remember when chairing panels involving opposing parties. As an example, Ripley highlights a frustrating effort (by Oprah Winfrey) to bring together Trump supporters and critics. By failing to explore tensions and contradictions within what speakers said, it seems Winfrey merely reinforced division.

One speaker on Winfrey’s show said:

“Every day I love him (Trump) more and more. Every single day. I still don’t like his attacks, his Twitter attacks, if you will, on other politicians. I don’t think that’s appropriate. But, at the same time, his actions speak louder than words. And I love what he’s doing to this country. Love it.”

According to Ripley, Winfrey could have responded by saying:

“Gosh Tom, I didn’t know from out of the gate that we were going to have this kind of complexity in the room… It’s so easy to say Yes or No, but you’ve actually said two things at the same time. So on the one hand, you love him more and more, and on the other hand, you don’t like some things he’s doing. Tell me what you don’t like about his attacks.”

As well as being useful when chairing debates, this advice might also be helpful to teachers mediating class discussions on controversial topics. It certainly reminds me of the approach I used to use during debates when teaching Citizenship.

Widen the lens

I’m not a big fan of the claim that we need to ‘have a debate about the purpose of education’, but Ripley’s next point might make me rethink this.

She points out the difference between two kinds of TV news stories: thematic, ‘wider-lens’ stories, exploring topics such as the causes of poverty compared to ‘narrow-lens’ stories that focus on a specific individual or event. It turns out that individuals who watch narrow-lens stories – for example about a “welfare mother” – are more likely to blame individuals, even if the story is compassionately rendered.

This surprises me. I’m generally keen to tell the individual stories behind school exclusion or pupils’ experience of material deprivation and how these play out in school. This is because I think doing so makes national issues tangible and real, helping readers empathise. Yet this seems to be at odds with the narrow/wide-lens finding.

Unpack motivations

Much of Ripley’s article is based on the work of mediators. One of the crucial things mediators do is ‘digging underneath the conflict.’

“(Mediators) have dozens of tricks to get people to stop talking about their usual gripes, which they call “positions” — and start talking about the story underneath that story, also known as ‘interests’ or ‘values.'”

Much of the argument about school exclusion seems to be premised on opposing values around whether we need to prioritise protection of minority rights (who I would tend to term ‘vulnerable’ minorities, and others might call ‘disruptive’), or whether we should ensure the majority does not suffer for a small minority. Different people sit at different points on the spectrum in relation to this question and I tend to find myself in the middle. Mediators would argue that the back-story behind the values leading to these views are key, and suggest that exploring these helps divided groups understand each other’s perspectives.

In my case therefore, I know that my school-life was strongly affected by the poor behaviour and invidious bullying that surrounded me at secondary school. I can’t help wishing the school environment hadn’t been so compromised by a troublesome minority. Yet, on the other hand I was brought up to value inclusion and to fight for minority rights. Meanwhile, nearly two decades working in the youth sector with disadvantaged groups has made me want to champion those who are so often ‘pushed out’. However, I also know that in the school I went on to work in, hundreds/thousands of pupils day-to-day lives were transformed when a ‘no excuses’ approach helped establish order and pro-educational attitudes. But I remain troubled to this day by the extent to which inclusion was compromised in doing so.

Understanding the back story behind my position may help others understand my ‘position’ and result in a more constructive discussion, even with those who disagree.

Ripley also highlights six moral foundations which are said to underpin political viewpoints:

- Care

- Fairness

- Liberty

- Loyalty

- Authority

- Sanctity

She argues that we need to “follow stories to these moral roots” and that journalists should speak to all six moral foundations in their writing. She proposes five questions that can help get to the heart of these questions:

- What is oversimplified about this issue?

- How has this conflict affected your life?

- What do you think the other side wants?

- What’s the question nobody is asking?

- What do you and your supporters need to learn about the other side in order to understand them better?

Better listening

One of Ripley’s interviewees is Lynn Morrow who works as a coach in university widening participation programmes. She explains that:

“We talk about what we’re comfortable and confident with first — and what you think the person wants to hear (but) when you really push them to go further is honestly when you get the most important information.”

As Ripley explains, people rarely “lead with their vulnerability.”

Morrow has therefore honed the art of spotting “gap words” – things that students don’t say, or when they hesitate. It is then that she digs deeper and repeats important questions. She also looks out for signposts including words like “always” or “never,” as well as any sign of emotion, use of metaphors, statements of identity, words that get repeated or any signs of confusion or ambiguity.

Ripley goes back to Winfrey’s Trump debate and highlights one man who said:

“We wanted somebody to go in and flip tables. We’re tired of the status quo…”

She suggests that an important question at this point would be:

“In your mind, what table got flipped?” or, even better “what tables have not been flipped”.

Secondly, Ripley suggests ‘looping for understanding’, a form of double-checking where you repeat back what someone has said, allowing them to clarify or confirm what they have said. She gives the following example:

Interviewer: “So you were disappointed by the Mayor’s actions because you care deeply about what happens to the kids in this school system. Is that right?”

Respondent: “No, I wasn’t disappointed by the Mayor’s actions; I was heartbroken.”

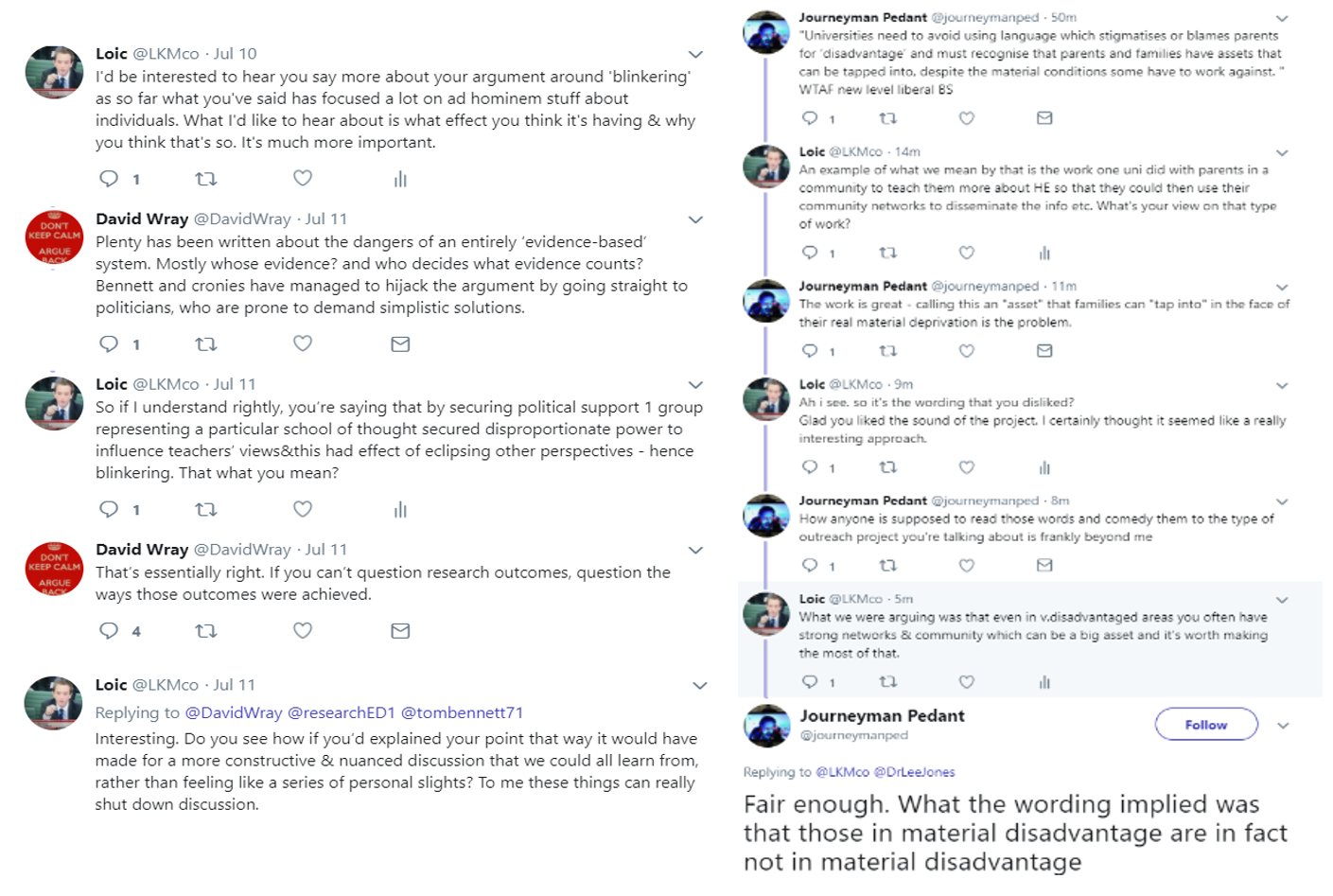

Perhaps this approach provides some lessons that can be used when talking to people with whom we disagree on twitter. It’s certainly something I’ve been trying to do more often recently. Even where I’ve initially felt defensive or angered, I’ve found that a deep breath and an effort to listen has rapidly helped move discussion onto a more positive footing.

Counter confirmation bias

Finally, Ripley points out that research into ‘confirmation bias’ shows that:

“People exposed to information that challenges their views can actually end up more convinced that they are right. (And more educated people are not necessarily less biased in this way.)… Confirmation bias is the Kryptonite of traditional journalism; it renders all of our most brilliant and meticulous work utterly impotent.”

Not only is this the kryptonite of journalism, it also threatens the very notion of ‘research impact’. Fortunately, Ripley highlights four ways of reducing confirmation bias:

- Use a range of sources that readers feel comfortable with.

This helps to reduce tribalism and makes it more likely that people will be open to a perspective. My article “Is No Excuses Inclusion Possible” for example, used arguments by both Nancy Gedge (from her book on Inclusion) and Katie Ashford (from The Battle Hymn of the Tiger Teachers), to make the same point- despite the fact that they both come from very different ideological perspectives. This hopefully helped a broad church of readers to feel there was something for them in what I was arguing.

- Graphics v. text.

Ripley cites a series of experiments by Professor Bernard Nyhan. These showed that presenting information visually increased the accuracy of people’s beliefs about “charged issues — including the number of insurgent attacks in Iraq after the U.S. troop surge and the change in global temperatures over the past 30 years”.

- Avoid repeating falsehood

Nyhan finds that it is important not to repeat a false belief in an effort to correct it. For example, rather than telling people that Barack Obama is not Muslim, they should be told he is a Christian, as the former bizarrely leaves many thinking that he is Muslim.

- Agency/hope

You have probably noticed that this blog is not about polarisation and intransigence in education debates, it is about what you can do to build constructive dialogue. This is because, as Ripley points out:

“When people are reminded that a problem has possible solutions (some of which they agree with and can act on in the near future) they are more open to considering the warning.”

Exposure to other tribe

Unfortunately, people from different ‘tribes’ don’t really hang out together very often. Yet ‘contact theory’ suggests that “once people have met and kind of liked each other, they have a harder time caricaturing one another”.

On the other hand, as our report “Encountering Faiths and Beliefs: The role of Intercultural Education in schools and communities” points out:

“It is not just the quantity of interactions that matters; effective intercultural education also depends on quality and in particular, on skilled delivery.”

Exposure, without the tools and approaches described above may therefore do little good, or even intensify conflict.

Ripley’s article helped reinforce something we’ve long tried to do at LKMco in terms of injecting nuance into education and youth debates. Ultimately, as Ripley concludes “People don’t want to be seen as callous. They want to be understood deeply.”

Read the full article by Amanda Ripley

Comments