Don’t forget the field! Why researchers should speak to teachers, parents and pupils

12th October 2018

“The distance between those in the classroom and those of us trying to help from the outside has increased exponentially”

These are the words of Karen Wespieser in her article “From Ivory Towers to the Chalkface” in today’s TES.

Karen is a researcher who has spent nearly twenty-years designing research and policy to help schools improve outcomes for young people. Her assessment is depressing but if she’s right, does it matter?

As someone who has spent the last ten years building up a self-declared education and youth ‘think and action-tank’ I certainly think it does, and one particular day, half-way through this year’s summer heatwave, reminds me why.

Visiting schools and communities

It was Tuesday lunchtime and I was once again on a train to a far corner of the country where I was due to deliver yet another of the hundreds of interviews and focus groups we conduct every year.

I stepped off the train and onto a platform in a small northern town and hunted for my connecting train. It was nowhere to be seen, and it seemed no other train would be departing said platform for another hour.

This wasn’t Cambridge, where a missed train just means a 15 minute wait until the next recently refurbished train zips you off to central London.

Around me, cursing parents shouted at screaming children. Fearing I’d be late for my case study, I leapt in a cab. As we made our way to the school we passed through abandoned ship-yards and docks before reaching a swathe of identikit estates that stretched for miles.

Finally we got to the school and I was dropped off in front of a shiny new block before I realised the bulk of the school was a bit further down the road on a very different and totally dilapidated site.

As I later discovered, it was due to have been demolished and rebuilt. But then Michael Gove cancelled the Building Schools for the Future programme.

Once in the school I met a group of pupils and we carried out a range of activities exploring their understanding of higher education, the relative merits of apprenticeships and degrees and their views on leaving, versus staying in their local area.

The focus group finished and I rounded it off chatting to a member of staff who railed against her frustrations with an education policy environment that she felt fetishized university degrees and devalued training routes like the one she had pursued.

Data in context

A few months later I was reviewing the synthesis of all the data we had gathered. It was a relatively quick study but included a handful of pupil focus groups, a survey targeted at low HE participation areas, a compilation of statistics from national datasets and a literature review.

As I read it I remembered my train journey, my taxi ride and my conversation with the students.

Was our write up true to what those students had told me? What could we say that would be useful to the people I met in that school? Were the solutions we proposed relevant to the communities we visited? Would our research ensure people in power heard the voices of the young people and teachers I’d spoken to?

Would our research ensure people in power heard the voices of young people and teachers? Share on XIn the last ten years, I’ve seen the availability of national data on education and young people improve immeasurably, as has the quality of analysis. This makes it far easier to highlight national trends, identify variation and to test hypotheses robustly. Indeed, if my fieldwork with those pupils had had to stand alone, it would have been far weaker. Our study, for example was based on an amazing dataset from the National Collaborative Outreach Programme. It identifies areas of the country where HE participation is low compared to what would be expected given educational attainment.

Being able to set our findings in the context of national datasets like this helped ensure what we said was not overly skewed by our own biases and perceptions on the day. However, as Karen argues:

That’s why our approach to research has always involved seeing the stories behind the data.

As Karen says:

“If you wanted to find out something about, say, teacher retention, you would need to conduct a large-scale survey and triangulate that data with case studies or interviews.”

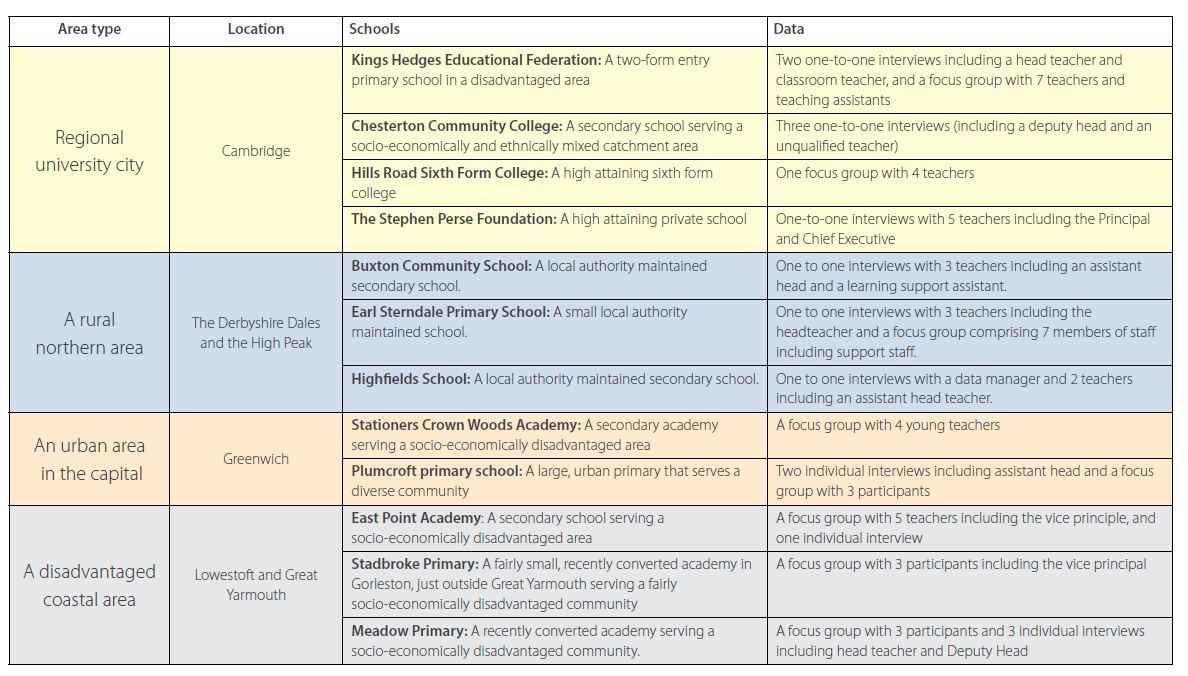

That’s why when I first became concerned about recruitment and retention I designed our “Why Teach?” study so that as well as a review of national statistics, it also included a brand new survey of nearly 1,000 teachers and detailed case studies of 12 different schools in four contrasting communities.

Doing so meant we could identify what was happening but also explore why, before telling the story of what we found out through the voices of the teachers we spoke to.

Meanwhile, one of the benefits of the detailed qualitative approach we took in our recent DfE study was that in spending 50 days in schools and manually attaching nearly 14,000 different thematic tags to 388 pieces of primary data, it was hard not to engage with the real-life experience of the parents, pupils and teachers we had met.

Involving practitioners at every stage

Now that we’re starting work on our next big study (this time looking at how to reduce the workload associated with assessment and develop teachers’ assessment expertise), the very first step involves identifying schools and teachers who are leading the way (Please get involved!) , and bringing together a group of head teachers and assessment experts to help us define our study’s focus.

Ever more sophisticated analyses of national data-sets provide us with unprecedented insight but shouldn’t blind us to the value of field-work that bridges the gap between researchers, policy makers and practitioners.

For me that’s an important part of why we exist. By digging underneath the pre-existing data; combining it with new evidence and our experience in the sector, we can reveal the full complexity of what is going on, whilst presenting it in a way that catalyses change.

Ever more sophisticated analyses of national data-sets provide us with unprecedented insight but shouldn’t blind us to the value of field-work Share on X

Comments