Reforming England’s Schools: The Rocky Road

by Loic Menzies

1st January 2022

Loic Menzies is the former Chief Executive of CfEY and is now working on a new book on education policy for Routledge. He is a visiting fellow at Sheffield Institute of Education, National Director at the Foundation for Education Development and a Policy Advisory to Cambridge University Press and Assessment’s Assessment Network.

Follow him @LoicMnzs

As part of my research for the book I’m writing (“How Education and Youth Policy Happens”) I’ve been reading Andrew Adonis’ book “Education, Education, Education” over Christmas.

Adonis’ book primarily focuses on the early days of academies, revealing a fascinating mix of ingredients that went into shaping the policy, including myriad factors that I’m exploring as part of my book. Right from the start though, I wished the book’s account was a bit more balanced. That feeling soon gave way to a nagging sense that the narrative needed to include a bit more of what happened next in order to give a true account of what it might really take to reform England’s schools.

Adonis’ book primarily focuses on the early days of academies, revealing a fascinating mix of ingredients that went into shaping the policy, including myriad factors that I’m exploring as part of my book. Right from the start though, I wished the book’s account was a bit more balanced. That feeling soon gave way to a nagging sense that the narrative needed to include a bit more of what happened next in order to give a true account of what it might really take to reform England’s schools.

A rocky road

I tweeted about the book extensively over the break and Dr Sam Sims asked if I’d be turning it into a blog. I hadn’t initially planned to because I was worried it could read like another round of ideological academy-bashing and I feared that trawling through the history of the schools Adonis mentions would be unhelpful; many are now achieving brilliant things against the odds and should be allowed to move on from their troubled past.

That said, I do think it’s worth casting light on the rocky road that lay ahead, since a 3D view is a prerequisite for anyone wanting to understand the challenges of system-level school improvement. I’ve therefore gone ahead, but avoided naming the schools explicitly (although I appreciate that most are fairly readily identifiable).

Adonis’ tale of reform begins with the initial crop of ‘independent state schools’, whose achievements he proudly catalogues. He describes their awe-inspiring designs, splendid learning environments and ambitious sponsors. Some, like Mossbourne have become household names that are shorthand for academic excellence.

Focusing in on one such school, Adonis recalls the opening of the awe-inspiring building and notes the new Academy’s immediate popularity. The school was immediately oversubscribed – though this initial flurry of parental excitement quickly evaporated, with enrolment falling by 25% within a few years.

While Adonis acknowledges that the premises were unnecessarily costly and required extensive repairs, I was surprised he didn’t mention the fundamental barriers to learning that came with a design that prioritised awe and glitz over practicality. This immediately raised alarm bells for me; I had trained with teachers who worked in the school and had heard bleak accounts of their battles to teach in the school’s open-plan classrooms. I therefore resolved to systematically check the examples cited in the book, against what happened next.

What I found was a bit depressing and can leave us in no doubt that transformation takes more than a change of structure.

'Transformation takes more than a change of structure' says @LoicMnzs Share on XWhat happened next?

By 2005 Ofsted knocked on the door of the aforementioned architectural triumph and went on to publish one of its first inspections of an academy. The judgement was damning. The school was graded ‘inadequate’ and standards were apparently significantly below average. It concluded that:

“HMCI is of the opinion that this school, including the sixth form, requires significant improvement because it is performing significantly less well than in all the circumstances it could reasonably be expected to perform.”

Yet 2005 is the very same year that Adonis describes as bringing “a string of positive verdicts… on the first academies”. He makes no mention of this wobble, or the evolution in the findings of different research studies on academies [1].

The book goes on to explore the possibilities that could be unleashed if other institutions were to make a habit of sponsoring academies.

First, Adonis points to private schools, drawing on the example of an academy sponsored by a leading public school. Delving into that academy’s story reveals that it is now judged ‘good’ but getting there has not been straight-forward. In fact, rather than the school’s governance being an immediate strength, when it was judged ‘Requires Improvement’ in 2014, governance was its Achilles heel. I’m sure the school had many strengths, but the involvement of one of the world’s most respected institutions doesn’t seem to have been enough to guarantee excellence.

Adonis identifies other institutions beyond public schools that could drive school improvement arguing that universities:

“Need to take responsibility for helping to transform the bottom half of comprehensive schools in two key respects: governance and… encouraging far more of their graduates to teach”.

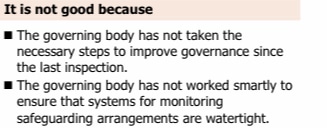

He illustrates his argument using a case-study of a high-flying university in the Midlands. This is unfortunate given that a year after the book was published the school was judged ‘Inadequate’. Clearly Ofsted judgements aren’t everything, but the narrative that emerges from the inspection is damning and the comments on governance are once again striking and at odds with Adonis’ overall thesis regarding the benefits of external involvement.

It is not just top tier universities that Adonis believes have the potential to transform schools. Next he turns to an academy that was sponsored by a former polytechnic in the South West. It now appears to be in a strong position, but only after it was taken over by a leading academy chain, having failed to get the support it needed previously. Once again, school transformation took more than handing control to an established and respected institution.

Leadership

If powerful backers are not enough to guarantee success, perhaps it’s the dynamic leaders that can come with them that really matter. Adonis turns to them next, hailing the Free School pioneers who built on the original academies policy. In doing so he mentions many of my own heroes, but once again, the truth is, things didn’t always go to plan.

Adonis dedicates two pages to one infamous South London school and its ‘remarkable’ headteacher, praising the way that income from the schools’ leisure facilities contributed to “wait for it – building a boarding school”.

What doesn’t make it into ‘Education, Education, Education’, because it happened soon after the book was published, is that the school’s boarding facility had to close down and – after protracted difficulties, another trust has had to take the school over and change its name. Despite the name change, the original trust and its Head are still regularly in the headlines due to ongoing legal battles regarding the school’s finances.

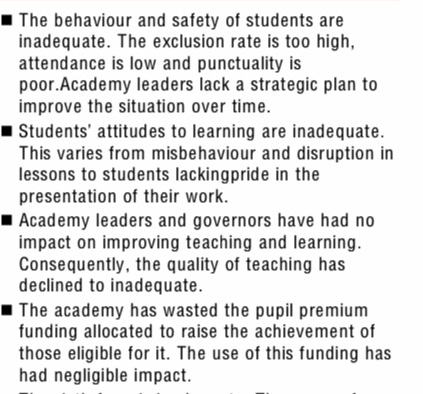

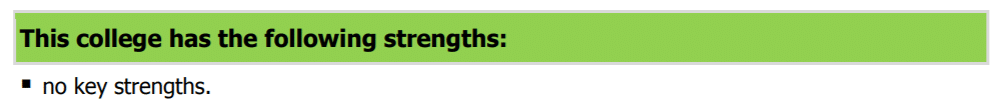

Two of the other entrepreneurial role models Adonis highlights also went on to secure more than their fair share of column inches. One led an early converter academy but was suspended following allegations of exam fixing. He was later cleared, although according to press reports, employees apparently complained of a “culture of intimidation” which they say left them feeling they had no choice but to cheat or leave. Meanwhile there have been calls for another of the leaders hailed as a pioneer to be stripped of his knighthood, since Ofsted reported finding “no key strengths” in the college he led. The local MP believes the CEO “starved it of resources and focussed on building a network of schools”.

It’s all a bit complicated…

I could go on – for example noting the distinctly patchy track record of the UTCs and Studio Schools that Adonis hoped would help put the nail in the coffin of the failing comp. Or perhaps highlighting the contrasting inspection judgements handed to the two academies that replaced one failing North London comp that was split across multiple sites. Adonis describes the one that was initially judged ‘Satisfactory’, but not the one that was initially ‘Inadequate’. Fortunately both are now ‘Outstanding’ and of course, there will be all sorts of reasons and challenges that sit behind those initial judgements.

In a way though, that gets to the heart of my point: none of these stories are black and white, and none of these struggles need detract from the success of so many academies – or schools like the one I taught at, which also happened to be almost next door to these two new academies. For all its various flaws, during the same time period it was classified as the 5th most improved school in the country and judged Outstanding – all while remaining under, and receiving excellent support from, the Local Authority and Diocese.

Having helped found a Free School, published Matt Hood and Laura McInerney’s now-famous model for how a fully academised system might work and conducted extensive research on academies’ visions and operating models, I am not a member of the ‘anti-academy brigade’. Instead, what I want to point out is that the reason school improvement is so endlessly fascinating and challenging is that it is both important and complicated.

'The reason school improvement is so endlessly fascinating and challenging is that it is both important *and* complicated' says @LoicMnzs of @Andrew_Adonis' book. Share on XAdonis’ book does a formidable job of emphasising the former but glosses over the latter – even positing that “almost all the solutions to big problems are simple” – and this does no one any favours. Being honest about complexity is surely a more helpful approach if we are to develop a more nuanced, and valid theory of change for reforming England’s schools.

What could that look like?

In his Chapter on “Why Academies Work” Adonis argues that “governance is the key” and that “independent sponsorship is the hallmark of academies and the secret of their success.” However he also acknowledges that “good governance and strong, ambitious leadership are only the beginning of what it takes to create a great school.” This is surely crucial and deserving of far more attention.

Great teachers, who teach the right thing in the right way matter immensely, and the fact that a sponsor has achieved success in other fields is not always enough to deliver all of those ingredients.

For what it’s worth, my theory of change for how academies might drive school improvement lies in the possibility of rebrokering when a school is persistently struggling (and where there is little prospect of improvement). This wasn’t an option back when Local Authority management was the only option. In fact, my research on London Challenge suggests that giving collaboration and support a hard edge was critical because it ensured there was a consequence if things failed to improve. The academy option provided that hard edge. Adonis makes some mention of the importance of rebrokering failing schools in an all-to-brief section on ‘what happens when academies fail.’ However, the real challenge right now is to finesse the mechanisms and structures for brokering and rebrokering effectively and efficiently.

'The real challenge right now is to finesse the mechanisms and structures for brokering and rebrokering effectively and efficiently' says @LoicMnzs Share on X

Adonis is rightly sanguine about the limitations of ‘evidence based policy,’ noting that ministers and officials:

“All professed to support ‘evidence-based policy’ but disagreed about the evidence…. When it comes to contested reform, consensus on ‘the evidence’ often follows years after the chance to act decisively upon it.”

Unfortunately, reviewing the stories Adonis uses to make his case suggests an approach to the evidence which is not just pragmatic, but verging on the cavalier.

This does a disservice to his overall mission, and the mission of countless education leaders who seek to transform the quality of education.

As Adonis himself says:

“Reasonable people differ, and progress generally follows a painful iterative process not a blinding flash of revelation. But that is no excuse for not rigorously seeking the truth by seeking out and weighing honestly the relevant data, research and experience.”

Only by being honest about both success and failure can we more successfully navigate the complex and challenging landscape of school improvement.

'Only by being honest about both success and failure can we more successfully navigate the complex and challenging landscape of school improvement' says @LoicMnzs Share on X

Comments