Maybe it’s because I’m a Londoner: the role of area-level factors in the capital’s success

19th July 2014

Can the remarkable improvement in London’s schools since the turn of the millennium be replicated elsewhere in the country, or was it underpinned by a set of contextual factors that are specific to London, and London alone? This is the question that observers will have in mind as they eagerly chart the progress of the various local and regional Challenges being established around the country. But for those with a hunch that area context matters, it’s important to be clear about what we mean when we talk about ‘area effects’: their derivation; their operation, and the way in which they are influenced by young people’s own understandings of the locality around them.

We explored the role of area context in our research for the Lessons from London schools report, by looking at whether improvement in educational attainment at local authority level was significantly correlated with three things in particular: gentrification, changes in labour market opportunities, and changes in ethnic diversity. We found that across London local authorities, gentrification and increasing density of jobs were both significantly related to improvement in GCSE attainment – explaining between 12% and 25% of the change in performance of London LAs. These aspects of area context were also significant outside London, but explained less of the improvement there.

Our analysis of these factors provides a useful starting point for considering some of the ways in which educational attainment might be shaped by area context. However, in exploring the role of local context there are three important things to bear in mind: how area-level characteristics are derived; the way in which these area-level characteristics produce individual-level outcomes, and how area effects are produced by young people’s own understandings of the areas they live in – not just our own objective definitions of those areas.

Firstly, as Friedrichs et al. argue, the central concern of any research into area effects should be to ascertain whether the characteristics of a neighbourhood exert an effect on the people who live there, even once we’ve taken account of the individual characteristics of those people (2003: 797). Today, the ONS is releasing its decadal update to the Output Area Classification (OAC), which assigns very small areas to particular ‘types’ of area based on the Census characteristics of the people who live there. The OAC offers a powerful way of describing the type of area in which a school, or set of schools, is situated, and arguably offers more nuance than deprivation scores: as Chris Gale demonstrates, urban areas that may share similar deprivation profiles vary widely in terms of area type. However, the OAC is derived from Census data – information about individuals – and arguably, to uncover true ‘area effects’ we need to refer to features of areas that can’t simply be reduced to the characteristics of the people who live there: things like local labour demand, the provision of services, and the state of infrastructure. Ken Roberts (2009) brackets these area level factors together as part of the ‘opportunity structures’ young people face in a given area.

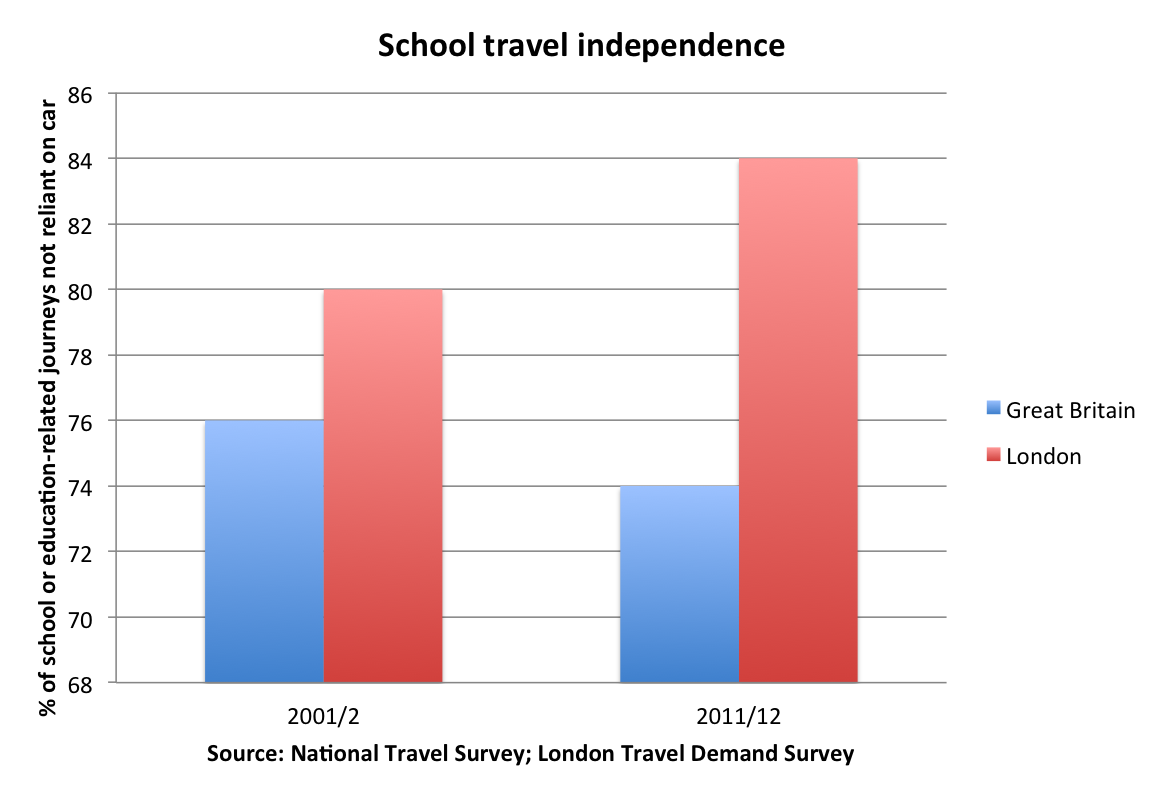

For example, during our research for the Centre for London/CfBT report we looked at travel use data by local authority, and found that young people attending secondary school in London are less likely to rely on their parents to get to school – and have become more independent during the past decade. This travel independence is likely due to the density of the capital’s public transport network, alongside schemes such as Zip Oyster which put the city’s various opportunities within affordable reach of most young Londoners.

Even once we’ve isolated the properly area-level factors that might shape young people’s educational outcomes, there’s a second point to bear in mind: we still need to give a decent account of how these area effects work. What sorts of mechanisms link area-level context and young people’s individual outcomes?

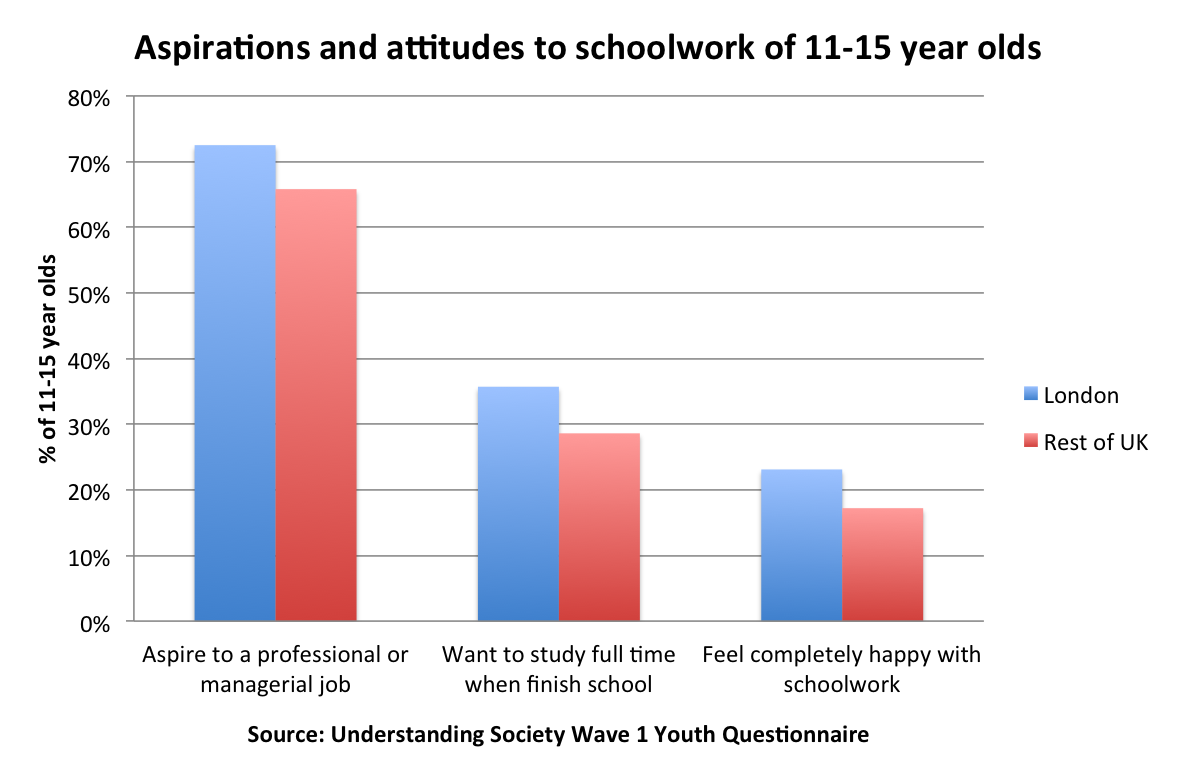

For instance, it might be that the transport component of London’s ‘opportunity structure’ could play a role in widening young people’s horizons, or giving access to information and experiences that facilitate their transitions from school to work. Using data from the Understanding Society dataset, we found significant differences between the aspirations and attitudes to schoolwork of 11-15 year olds from London, and the rest of the UK. As Lupton suggests, these aspirations and attitudes might function as mediators between local opportunity structures and young people’s educational attainment (2004: 16) – in short, they’re a potential candidate for explaining how area characteristics shape individual level outcomes.

A third and final consideration enters the mix when we’re talking about area effects on young people’s individual outcomes: most of our accounts of area interpret ‘area’ objectively – with features picked out and classified by statisticians. But what about young people’s own experiences and appraisals of the areas where they live and go to school? The young people who live in a given geographical area will all have different understandings and interpretations of that area, which will in turn produce different attitudes, motivations and behavioural responses – potentially feeding into a variety of educational outcomes.

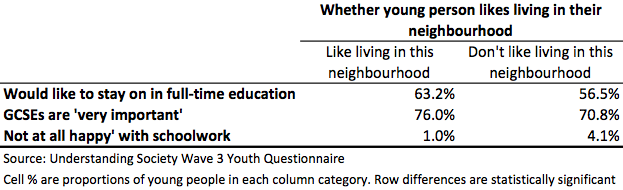

For instance, Wave 3 of the Understanding Society dataset asks a nationally representative sample of young people “do you like living in this neighbourhood?”, and there are some statistically significant differences between the aspirations and attitudes of young people who respond positively, and those who respond negatively.

While these attitudinal differences aren’t huge in magnitude, they indicate the ways in which young people’s individual-level outcomes can be shaped by their affective orientations towards the areas they live in. And this puts us one step closer to identifying the mechanisms that link the two.

In order to assess the role of area context in shaping young people’s educational (and other) outcomes, then, there are three things we should strive to do:

1) Identify truly area-level characteristics, rather than just aggregations of the individual-level characteristics of the people who live in an area

2) Try to identify the mechanisms that link particular area-level features with particular individual-level outcomes

3) Consider how young people interpret and understand their area context, rather than relying exclusively on objective definitions

The debate will continue as to whether London schools’ dramatic improvement was underpinned by a specific ‘London effect’. Regardless of this, the myriad subtle differences that exist between areas mean that simply transposing the London model of improvement is not a viable option for the various local and regional Challenges now being established. Sensitivity to the particular characteristics of these areas, as well as how the young people who live there interpret and interact with them, will be crucial.

More London blogs:

Collaboration: it doesn’t happen by magic

How London learned from its teacher shortage

Professional development and professionalism: The symbolic roleof CPD

Show me the money: Was London’s success all about the extra money?

More than the sum of its parts: How London’s boroughs helped drive success

London Schools: Now we have a full(er) picture

‘Lessons from London Schools: Investigating the Success’ is a Centre for London and CfBT report and we are grateful to both organisations for giving us the opportunity to carry out an in depth study of this crucial topic.

The views in this blog are my own and whilst my analysis is predominantly based on the CfL/CfBT report, not all the data I have presented here is necessarily in the report.

Comments