Play-based Learning in Finland: Why it Matters

3rd February 2016

“If [it’s] minus 15 [Celsius] and windy, maybe not, but otherwise, yes. The children can’t learn if they don’t play. The children must play.” – Principal of Kallahti Comprehensive School, Finland

Should play matter? And does far-off Finland have anything to teach us about that? I think, the answer to both questions is yes.

I recently had the privilege of listening to Professor Kristiina Kumpulainen speak about play in Finnish education at Cambridge University. Finland has captured the interest and imagination of researchers and policy-makers around the world due to its impressive performance on international benchmarking tests (although recent years have seen a slight drop in rankings). Professor Kumpulainen explains that Finland’s results are particularly exciting for many in education, because students achieve highly, despite starting school at the relatively late age of 7, despite having shorter school days, despite the fact that teachers and local authorities have far greater autonomy than many of their high-performing rivals… and, she argues, despite the fact that play features so powerfully in Finnish education.

Huge controversy surrounds attempts to compare countries’ performance using international benchmarking tests and speculation is rife as to what has played the greatest role in shaping Finland’s current educational landscape. Some argue that Finland’s recent drop in ranking is due precisely to the shift from traditional, teacher-centered learning to more progressive, pupil-centered styles, whilst others argue it is a broad swathe of cultural factors rather than one easily isolated variable (such as play), that brings educational success. It would also be rather hasty to argue that Finland and England are completely dissimilar with regards to their perspectives on play; not all Finnish schools are equally big on play, and England is by no means completely “anti-play”. Nonetheless, Professor Kumpulainen’s talk very valuably challenged my preconceptions as to what play is, and why play matters.

Why does play matter?

Professor Kumpulainen gives two main reasons why play matters:

- Our understanding of learning has changed. Current research demonstrates clear relationships between experiences of play, and social and self-regulatory skills and academic achievement (see also this).

-

It is increasingly hard to predict children’s career trajectories, or expect, as we did less than half a century ago, that they will have a single job over the course of their lives. Education must respond to these changes, and equip students with the competencies not only to receive knowledge, but to engage in creative problem-solving and to exercise resilience and flexibility in these new conditions. Play helps develop these skills.

Definitions are half the battle

Research has defined play as an immersive activity that engages one’s senses, and which one can enjoy, care about and feel strongly about. Play respects students’ interests and strengths. It simultaneously allows the child to take some degree of control, while requiring some sort of external, adult input to guide the child toward holistic development. Because children only start school when they are 7, pre-school education can maximise opportunities for play – and pre-school education in Finland deeply values play. In fact, Professor Kumpulainen also revealed that Finland has recently considered extending playful learning to older children and even adults.

Professor Kumpulainen highlighted different forms of play and argued that it was therefore wrong to equate play with an anything-goes free-for-all. Play might include:

- Free play,

-

Peer-led play,

-

A rule-based activity.

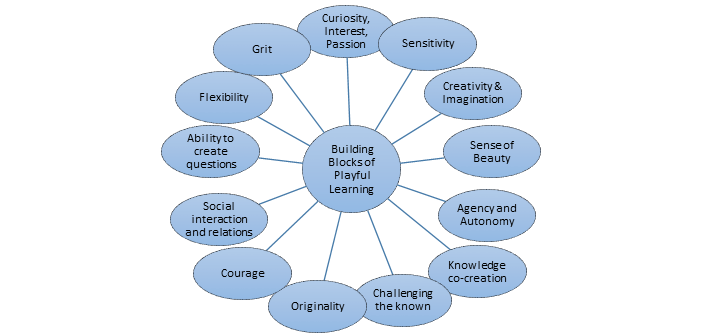

She emphasised the following building blocks of playful learning:

I don’t think Professor Kumpulainen was advocating the disappearance of hard work, rigour, and achievement. Instead she was arguing that the best way to achieve all three is to value play in early learning. Policy-makers and practitioners would do well to consider the Finnish approach afresh. Whether or not play gets us better (academic) results, when we marginalise play, society loses something crucial to its flourishing and growth.

Comments