The London Schools Effect revisited: A saga in many parts

by Loic Menzies

7th February 2021

Writing in Schools Week earlier this month, my colleague Baz Ramaiah bemoaned a tendency for education research to focus on novelty at the expense of replication, highlighting the pernicious effect this has on the evidence base.

One area in which there has been no shortage of studies, is the so called ‘miracle’ of London schools’ surprisingly high performance, and last November, a crucial new contribution to this ever growing body of work was made by Lessof et al. Their work means we might finally understand some of the mysterious mechanisms that have gone into making England’s capital an international exemplar. It also provides invaluable lessons to anyone looking to improve educational achievement among disadvantaged pupils.

Before we go on to this latest contribution and the lessons it provides, let’s start by re-capping the last few episodes in a saga that has gripped the academic community for the best part of a decade.

First forays

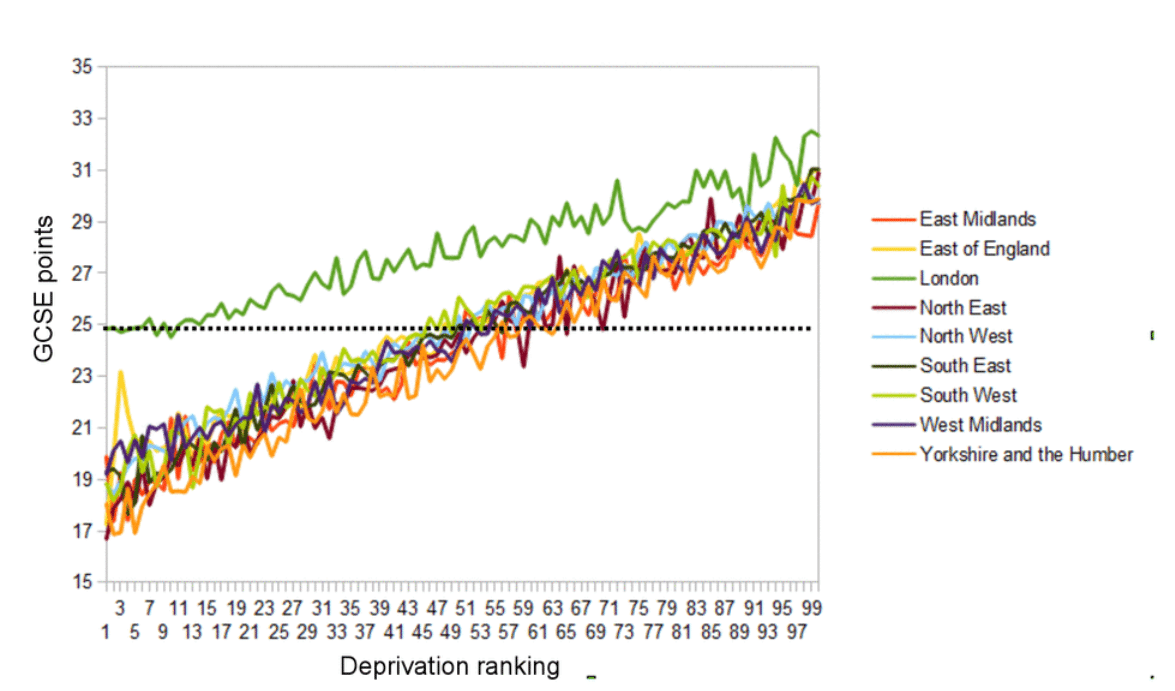

The story begins back in 2012 when Chris Cook – then education editor for the Financial Times, began playing around with the National Pupil Database, producing colourful graphs that pulled the plug on years of rhetoric about the capital’s ‘sink schools’.

His analysis showed that London’s pupils were leagues ahead of their peers elsewhere in the country when you took into account deprivation levels. This trend is replicated in Lessof et al.’s new analysis which shows that the capital’s disadvantaged pupils averaged eight GCSE grades higher compared to FSM pupils elsewhere in 2015.

Inspired by Chris’ work, I worked on one of the early studies of the London advantage alongside my CfEY colleagues, in partnership with The Centre for London and CfBT (now the Education Development Trust) .

Our study identified 27 different hypotheses that might explain the ‘London advantage’ and we investigated each of them in turn.

Our conclusion was that London’s schools existed in a particular context which shaped pupil performance but that this couldn’t, on its own, explain what was going on. Instead, we thought schools had improved dramatically once fertile soil had been laid through the dismantling of barriers to success (like difficulties with teacher recruitment and the historic lack of funding). We argued that success ensued once these propitious circumstances were combined with a collective moral purpose, data-driven collaboration and sense of possibility, as well as concerted action wherever under-performance was identified.

In sum, we thought the key drivers behind the ‘London Advantage’ were education policies and school practices which were not unique to London Challenge, but which reached their zenith in this famous school improvement initiative.

Whilst its always nice to see advances in knowledge and research, I’d be lying if I didn’t admit it was a little galling when our conclusions were thrown into question by those armed with better data.

Before we even had time to publish our findings, the inexorable march of progress took a step forward with a new study led by Ellen Greaves. Ellen and her colleagues concluded that differences in Key Stage Four attainment were in fact largely explained by Key Stage Two attainment.

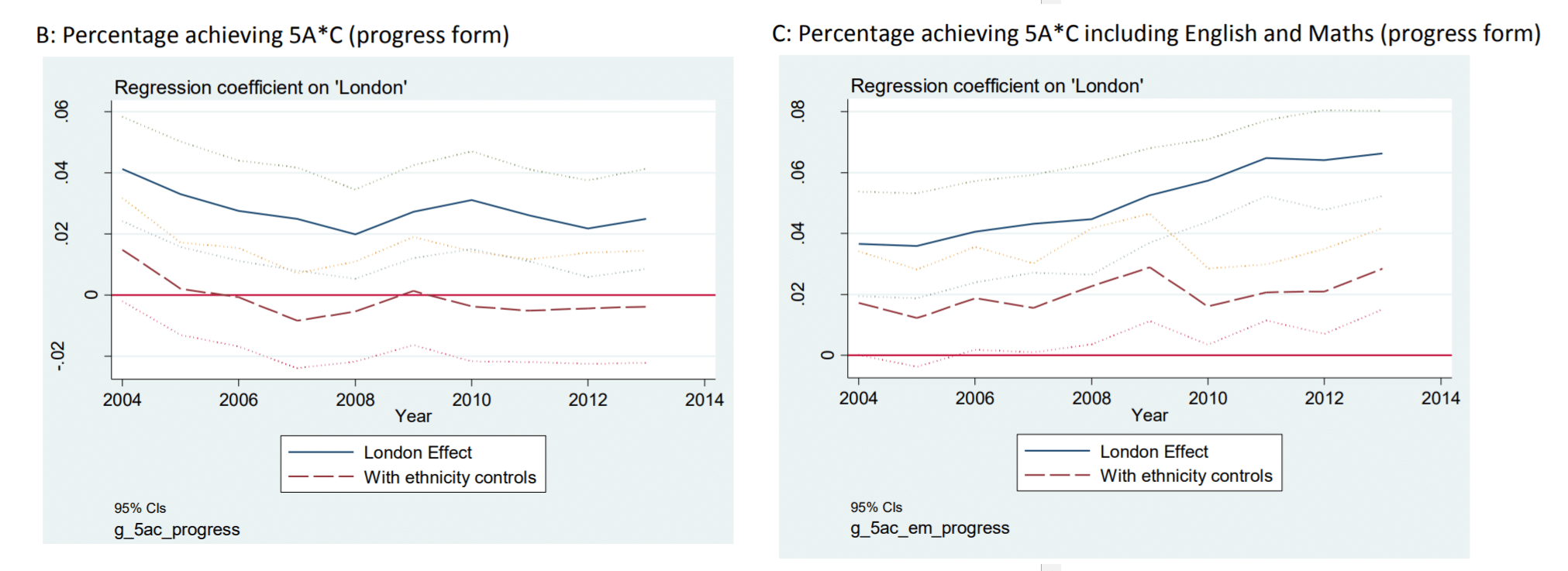

Study followed study, and in turn, Greaves’ own conclusion was thrown into question in a paper by Simon Burgess published later that same year. Burgess’ paper blew everything out of the water by showing that most, if not all (depending which measure is used), of the London effect could be explained by differences in ethnicity.

Yet the debate never fell silent and much of it hinges on that question of ‘most v. all’. In other words, does pupil background explain the whole advantage, or just a large part of it?

Every time someone cuts the data a different way or uses a different attainment measure, this crucial ‘percentage of variance explained’ shifts.

So, the question keeps coming back: might London schools be doing something special?

The question keeps coming back: might London schools be doing something special? Share on X

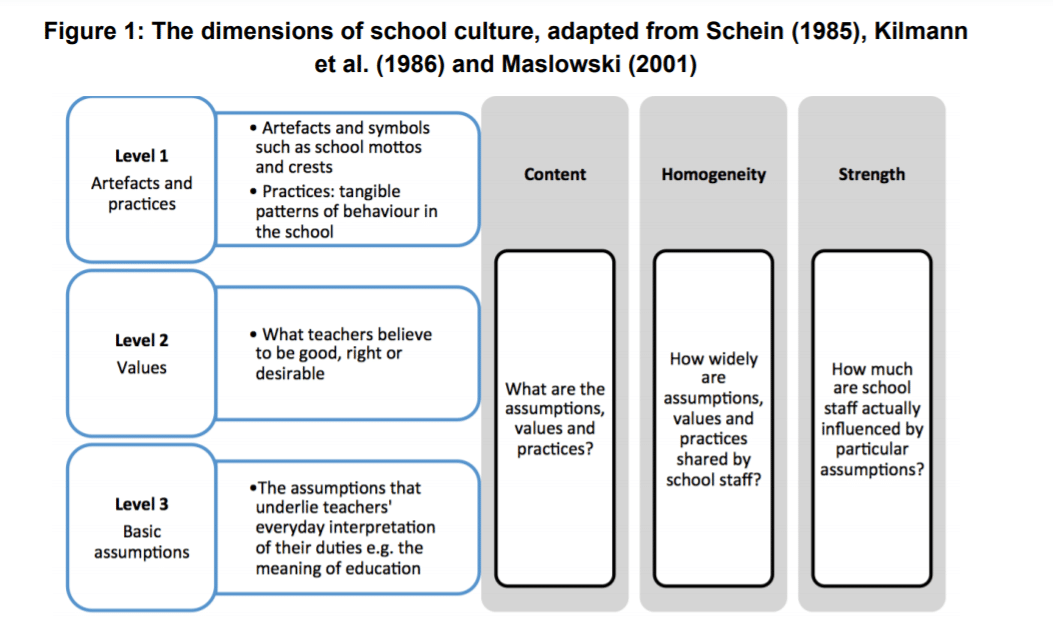

The role of schools culture

We all know that palpable sense of culture you get when you walk into some schools. My colleagues and I therefore turned to look at that next, as part of a large DfE funded study published in 2018. Our research involved spending day after day observing classrooms and playgrounds, as well as talking to parents and pupils in high and low performing schools in London and elsewhere.

Eventually, after coding nearly 10,000 excerpts of data, we concluded that although we found distinctive cultures and practices in high-performing schools, distinctions between London schools and those elsewhere did not constitute a conclusive explanation of any remaining effect.

Fortunately, the DfE did not just fund one study and, as 2020 drew to a close, Lessof et al., gave us the Christmas gift of a whole new ream of analysis. Their fascinating report explores attainment and progress, both in 2006 and in 2015 using evidence from the Longitudinal Study of Young People in England (LSYPE).

A whole new level of analysis

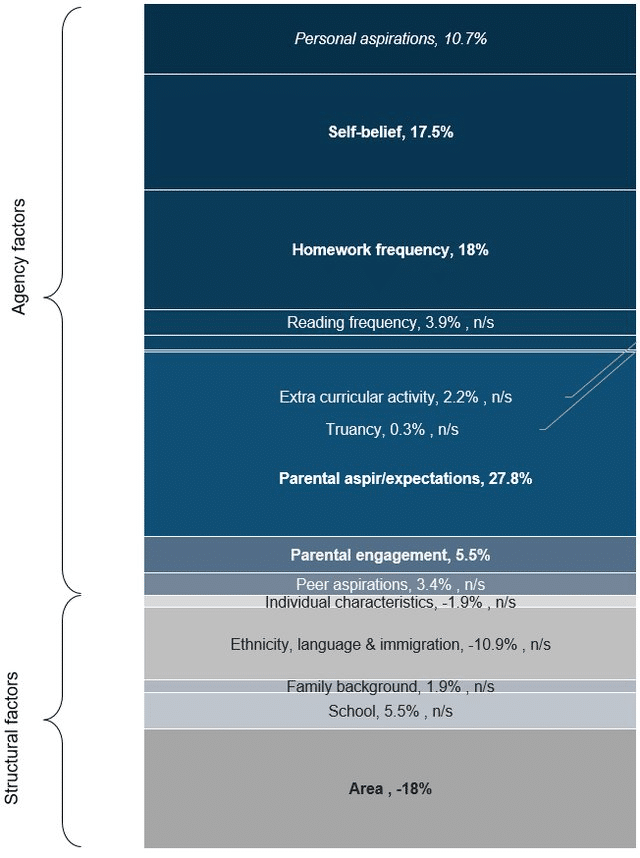

Lessof and her colleagues focus on the role of ‘structural’ and ‘agency’ factors.

According to their paper, structural factors include:

- Ethnicity, language and immigration status (considered separately and together);

- School characteristics;

- Area deprivation; and,

- Pupil and family characteristics.

The authors consider these to be “relatively immutable.”

Next, they add in agency factors, such as:

- Homework completion;

- Risky behaviours;

- Self-belief; and,

- Aspirations

Their rationale is that if the effect of structural factors falls when you add in a related agency factor, it provides a hint that the structural factor might be ‘mediated by’ the agency factor.

In other words, if the effect of ethnicity drops when you add in homework completion (as it does), then part of the reason ethnicity explains so much of the London advantage might be that pupils from certain ethnic groups are more conscientious about doing their homework (or that this homework completion is a handy indicator of some sort of ‘pro-school attitude’).

The study concludes that a powerful cocktail of pupil and parent expectations and aspirations, homework completion rates and low rates of involvement in risky behaviours largely explain London’s progress advantage in 2006.

A powerful cocktail of pupil and parent expectations and aspirations, homework completion rates and low rates of involvement in risky behaviours largely explain London’s progress advantage in 2006 Share on XChanging determinants of attainment

The study’s comparison between 2006 and the state of affairs roughly a decade later is particularly useful, and the differences are striking.

Back in 2006, differences in truancy and risky behaviours between disadvantaged London pupils and those in the rest of England accounted for a sixth of the London advantage in attainment (something which might come as a surprise to anyone associating these behaviours with the big-bad city). However, as levels of truancy and risky behaviours declined across the country, these factors’ contribution to London’s attainment premium fell to almost zero. On the flipside, worsening area-deprivation (i.e. increased poverty) served to depress attainment in the capital.

Low rates of risky behaviours like truancy in London compared to elsewhere might come as a surprise to those picturing a big bad city Share on XWhile Lessof et al.’s report primarily focuses on factors that do explain the London advantage, right at the end, there’s also a fascinating list of factors that do not. These include:

- Involvement in extra curricula activities

- Family life

- Self-reported school experiences such as relationships with teachers and bullying.

So what?

This latest study won’t be the final word in the saga of explaining the London advantage. In fact it raises a number of questions and the data can always be cut any number of different ways; CfEY’s recent study with Manchester Metropolitan University suggests that absence rates at Key Stage Three are closely linked to declining progress amongst disadvantaged pupils as they transition to secondary school. Lessof et al.’s treatment of unauthorised absence as a “relatively immutable” structural factor therefore seems somewhat defeatist as it is exactly the sort of lever schools and other agencies could work to change.

Similarly, if homework really is so important (causally or as a proxy for something else, we don’t know), what role might there be for schools here?

These questions matter deeply because they shape the ‘so what?’ for schools. If it’s the pro-school attitudes and behaviours linked to ethnicity that explain the London advantage, then we might want to revisit how these attitudes and behaviours might be nurtured. Doing so comes with a note of caution though, since researchers like Stephen Gorard and Beng Huat See have shown that interventions in this area (of “AABs”) are a real minefield when it comes to evidence.

Ultimately, more research is almost always needed, but Lessof and her colleagues have certainly provided a compelling new chapter in this most enduring of sagas.

Comments