Waving bye to CfEY

by Sam Baars

6th April 2022

Today I’m moving on from the Centre for Education and Youth. Reassured by all the research I’ve done over the years on how people formulate and pursue their occupational aspirations, and how it’s normal for our plans for the future to sometimes be loosely defined or unclear, I’m embracing the fact that I don’t currently know what I’m going to do next.

Whatever the future holds, I feel immensely fortunate to have spent the last eight years working alongside such a brilliant, committed team, and I’ll always look back with great pride on the things we’ve achieved together. Being part of the CfEY team has allowed me to find my voice as a researcher, see how powerful and practical the outputs of robust research can be, and learn the art of maintaining a creative and supportive organisational culture where people take their work seriously, without taking themselves too seriously.

I can think of many highlights from the last eight years, but guided by our policy team’s legendary Friday Fives, here’s my fistful of favourites.

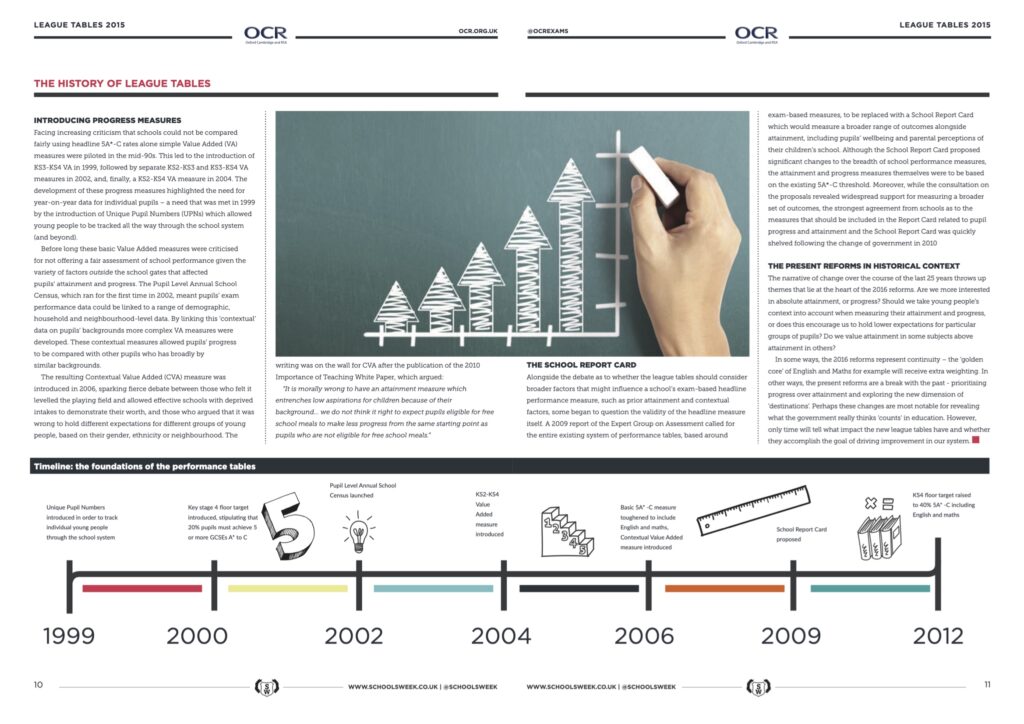

In 2015, during the last big shakeup of school accountability measures, I wrote a piece on the history of league tables for Schools Week. It was my first experience of writing a policy history (I followed up with one on the history of baccalaureates and diplomas). I treated it like a piece of investigative journalism and got completely carried away. The highlight for me was uncovering a DfEE press release from 1995, heralding the moment when performance tables were made available online for the first time as “the biggest public information exercise ever undertaken by any government department.” I’ve always remembered that quote – it’s a reminder of how the tools we have to explore the social world are transformed with the passing of each human generation (and of just how excited people got about the internet in 1995).

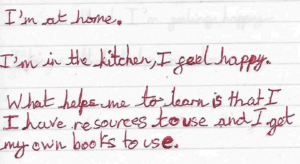

Between 2016 and 2018 I led our first major project for the DfE, looking at how school cultures and practices support the attainment of disadvantaged pupils. This was a true mixed methods project, using pioneering statistical analysis to guide a set of 23 in-depth school case studies. Over the course of two years the CfEY team conducted 388 interviews, focus groups, walking observations and pupil diaries across the length and breadth of the country. We worked together to systematically apply 14,000 thematic tags to our data, yielding groundbreaking insights into how teachers and leaders foster whole-school cultures and practices to support their pupils. I can vividly remember the night I stayed up until 5am, fixing erroneous hyphens in the final draft. I still see the report as one of our crowning achievements: a true team effort, an outstanding piece of empirical research, and a rare example of a government report featuring young people’s own felt pen reflections.

Six months after the publication of our landmark report for the DfE, I was reflecting on school cultures and practices in a far more personal capacity. My blog on school choice shared my experiences of getting to know schools as a parent, rather than a researcher, and became my most-read blog at CfEY. My daughter Ida is now thriving at the school I featured in the blog, and my regular Friday reading groups at Downsbrook are one of the highlights of my week.

Big thanks @frankcottrell_b for your excellent postcard to the Year 6 reading group at @dpsworthing. It made us laugh a lot. As did this passage about Frothy Coffee People. #books #reading #literacy #Worthing pic.twitter.com/v1SCeKhdXv

— Dr Sam Baars (@sambaars) January 14, 2022

My final highlights relate to my two long-running research interests, which I’ve had the chance to take off in all kinds of directions during my time at CfEY: aspirations and area effects.

On a chilly February morning in 2015, I took to the stage with Eleanor Bernardes at the Schools North East FutureReady conference to deliver a presentation debunking eight key myths about aspirations which riddled policy and practice at the time, drawing heavily on the empirical work from my PhD.

An overview of the 8 aspirations myths I dispelled today with @Nor_edu @SCHOOLSNE #FutureReady15 pic.twitter.com/Nn526SxpIV

— Dr Sam Baars (@sambaars) February 11, 2015

Slide by slide, we presented evidence to counter the received wisdom about ‘low aspirations’, the assumed stability and certainty of young people’s hopes for the future, and the conflation of aspirations and expectations. We were followed immediately by a pitch from a careers advice company, selling a package to schools which was based entirely on the very myths we’d just carefully dismantled. It was an awkward experience, but also hugely energising: it showed that four years of fieldwork and statistical analysis, and six months of writeup in a solitary office at the University of Bielefeld, had been worth it. Key assumptions at the heart of education policy, social mobility strategy, careers guidance and teaching practice needed overturning, and we had the evidence and platform to do it. We caught the ears of more and more practitioners in the months that followed, and before long we’d embarked on what Eleanor and I came to call the ’aspirations roadshow’ which took us, and our slides, the length and breadth of the country. My work dispelling the aspirations ‘myths’ was a formative experience for me: it showed how evidence generated in academic circles can often entirely fail to cut through to the world of practice; how easily received wisdoms take hold in its place, and how open teachers and leaders are to new ideas that challenge their existing practice, if those ideas are relevant, engaging and well-evidenced. In a 2019 opinion piece, I finally felt able to declare the ‘raising aspirations’ discourse dead.

During my eight years at CfEY we’ve also done pioneering work exploring how young people’s lives are shaped by the areas they live in. Place-based research and policy is, without doubt, the stuff that makes me tick. In a 2015 piece for the New Statesman I made the case for talking about different ‘types’ of area, rather than more and less deprived areas. I showed how young people in deprived outer urban areas make vastly less progress at secondary school compared to their peers living in similarly deprived inner city areas. I’ve since continued to argue for more focus on young people growing up in the types of neighbourhood you find on the edges of cities, in small and medium-sized towns, in the hinterlands that get missed by every passing Area Based Initiative. Our report on youth transitions in Buckinghamshire provided me with a canvas to illustrate some of these ideas at a local level. My mapping showed how in an affluent home county, many young people can nonetheless find themselves isolated from infrastructure and opportunity and struggling to make the transitions they want to.

In our 2021 book Young People on the Margins I set out practical, evidence-informed ways we can break out of the decades-long cycle of failed area-based policymaking in education. The announcement of Education Investment Areas as part of the 2022 Schools White Paper gave me reason to rehearse these arguments once again.

My interest in outer urban areas of deprivation also means I’m never far from the ‘white working class underachievement’ debate, and I’ve tried to use my media appearances to take some heat out of the culture wars.

There are tons of state schools doing brilliant work with young people who struggle at school; supporting them to achieve great things. We don’t need to expand grammars. We don’t need to expand private schools @GBNEWS @GloriaDePiero @LiamHalligan pic.twitter.com/6Y9ELQeaQf

— Dr Sam Baars (@sambaars) November 18, 2021

I want to end with a shout out to Joe, who took over as our CEO in October, and the rest of our senior team: Ellie, Bart, Will and Gemma. There’s a special kind of comradeship that comes with working in a small, close knit team. At times it’s felt like sharing a storm-battered life raft. But one with a seemingly endless supply of graft, quick thinking and wit*.

What a fantastic blog to end your time at CfEY. You’re rightly proud of your brilliant report for DfE on school practices and cultures in high-performing schools (where our paths first crossed!) amongst a long-list of other knock-out achievements. I’d love to get you along to EPI to give a talk on area-based approaches, though appreciate you might be having adventures in far away lands or just enjoying a bit of time out. Best of luck for whatever the future holds Sam.